First Thoughts on Spike Lee: Creative Sources at BK Museum

When PAUSE with Sam Jay premiered on HBO Max in 2021, it pioneered a new format. Imagine a Black millennial house party: red cups, a spades table, a foil pan of macaroni and cheese (the good kind), and a lot of people making their point stick by simply being the loudest person in the room… all crammed into a New York apartment. The episodes swapped between house party antics and sketches centered on a theme and as a quarantined viewer during the isolation of COVID, it was comforting to see people so close to each other and so animated. I imagined I was there, breathing pre-COVID air, throwing my head back in laughter during a (much) simpler time. While all the partygoers weren’t Black, it felt like a Black space…at first. In the premiere episode entitled “Coons” the partygoers discussed the question, “Is Spike Lee A Coon?” and I imagined myself leaving the party early to get some air. It had never occurred to me that this was even a possibility. Spike Lee, the prolific and consistently overlooked Black filmmaker, everybody’s favorite Brooklyn uncle, the Knicks number one fan, the Morehouse Man – who could be more “for the people” than Spike? How could the man who untangled interracial dating (Jungle Fever), promoted women’s sexual agency (She’s Gotta Have It), critiqued colorism and the violence of Greek Life at HBCUs (School Daze), gave Black heroes the biopic treatment before it was a thing (Malcom X), reignited a discourse on interracial violence (Do the Right Thing), and who is staunchly anti-buffoonery be seen as a discredit to the culture and a docile elder?

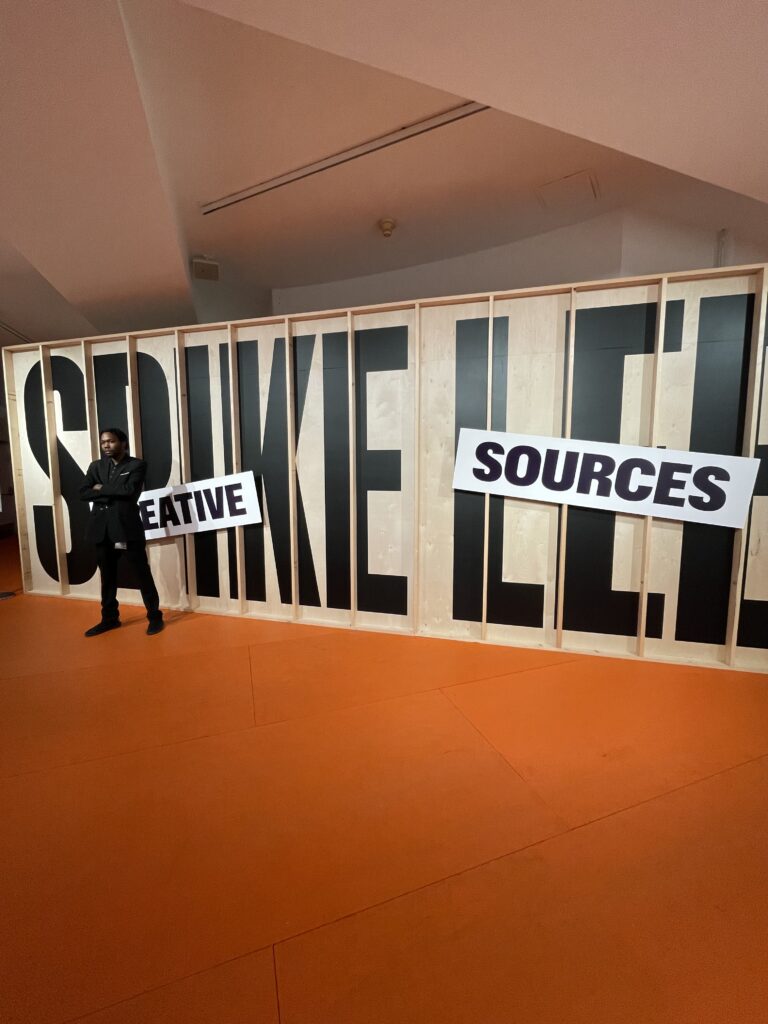

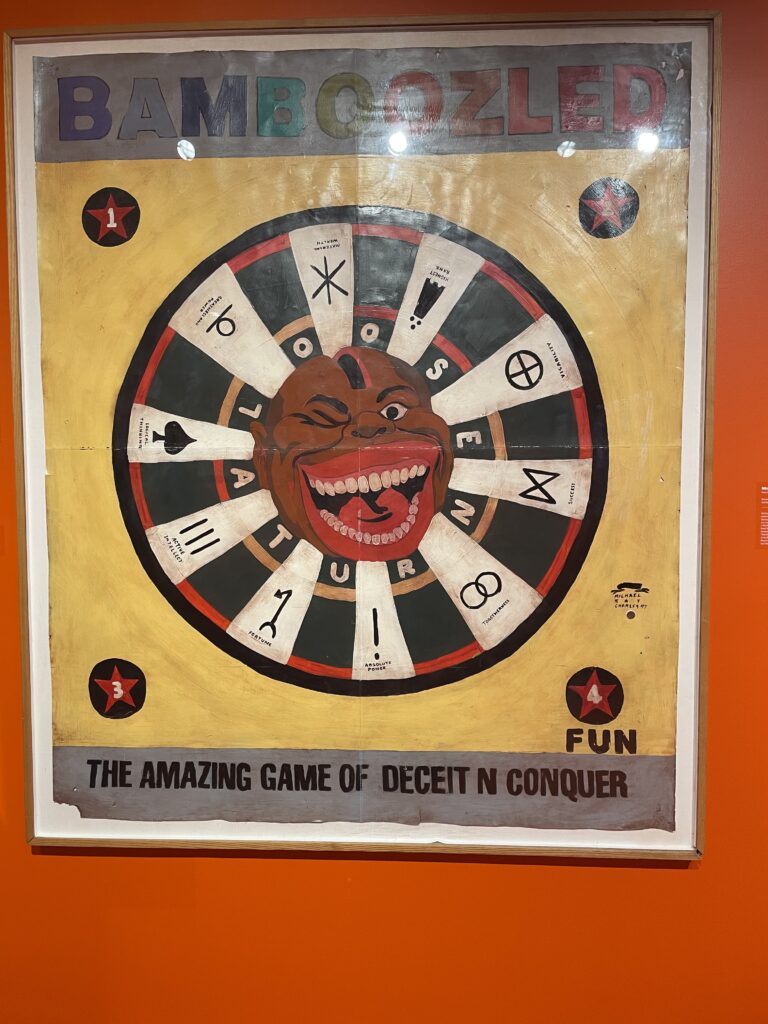

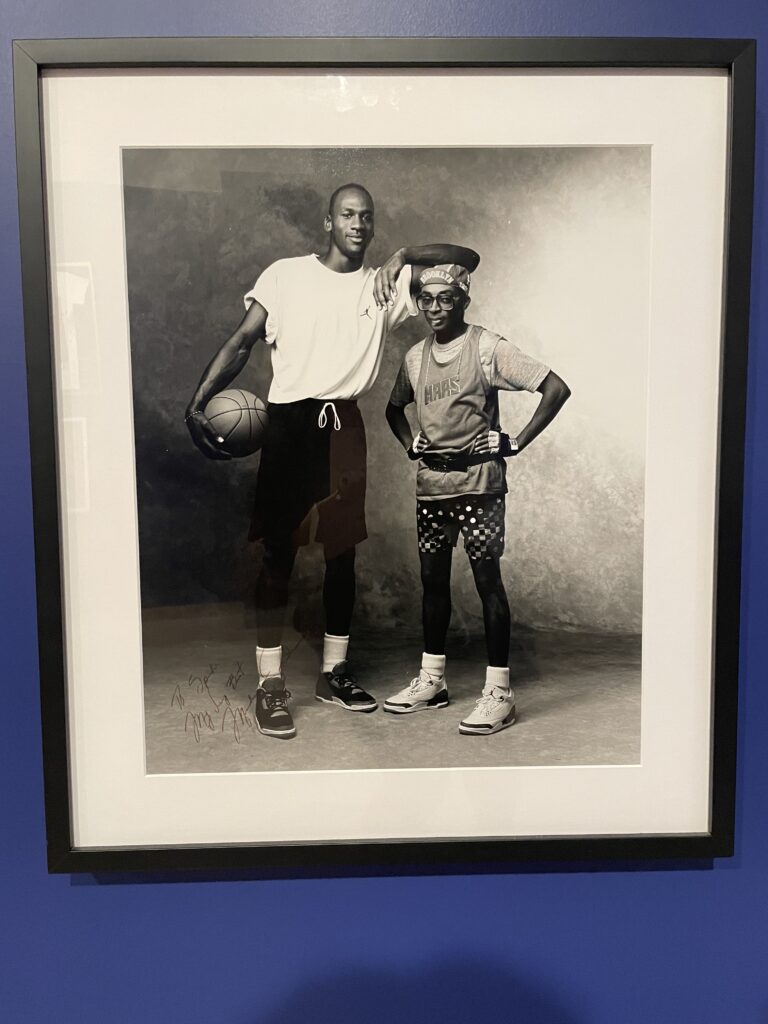

Until I’m invited to Sam Jay’s next party, I’ll be preparing my bullet points. But in the meantime, Spike Lee: Creative Sources at the Brooklyn Museum allows the viewer to decide. At the start of the 7-room exhibit is note that explains that everything on display belongs to Spike and Tonya Lewis Lee, his wife. It’s expected that the outfits (like the one he wore to chair the Cannes Film Festival) and movie props (like the G PHI G varsity jacket from School Daze) and mementos (a signed inmate ID card from Michael Jackson) would come from his own collection, but then there are some truly valuable pieces from other Black artists in his private stash. Toni’s Morrison’s 1st Editions and the portrait he commissioned from the Time magazine cover, Prince’s guitar, a Kehinde Wiley portrait, a Basquiat drawing, original photos of Muhammad Ali and Nelson Mandela, a bust by sculptor Augusta Savage, and more are enough to tell a story separate from Spike. And then there is the BTS content for the films: his jazz musician father composed most of the scores, there are handwritten, leather bound copies of the scripts, Rosie Perez’s opening dance scene from Do The Right Thing which plays on a loop took 8 hours to film. These artifacts, sorted into the categories of Black history and culture, family, Brooklyn, photos, cinema history, music, and sports are his creative sources, his inspiration. There’s a certain degree of reverence required for the value of the items on the walls – both financially and culturally – but Spike’s humility is spread across all of the items he asked other big names to autograph. There are signed game tickets, movie posters, artwork and personal letters. The mental picture of Spike paying homage to his contemporaries — being a fanboy and asking a famous person for a picture or a signature — is endearing. Standing in the exhibition fully immersed in both the mind of Spike and the legacy of Black excellence, you can see the man behind the lens.

Zoom in on whether he measures up to your expectations for Black artists over jerk pork and Caribbean libations at The Rum Bar around the corner on Franklin Avenue.