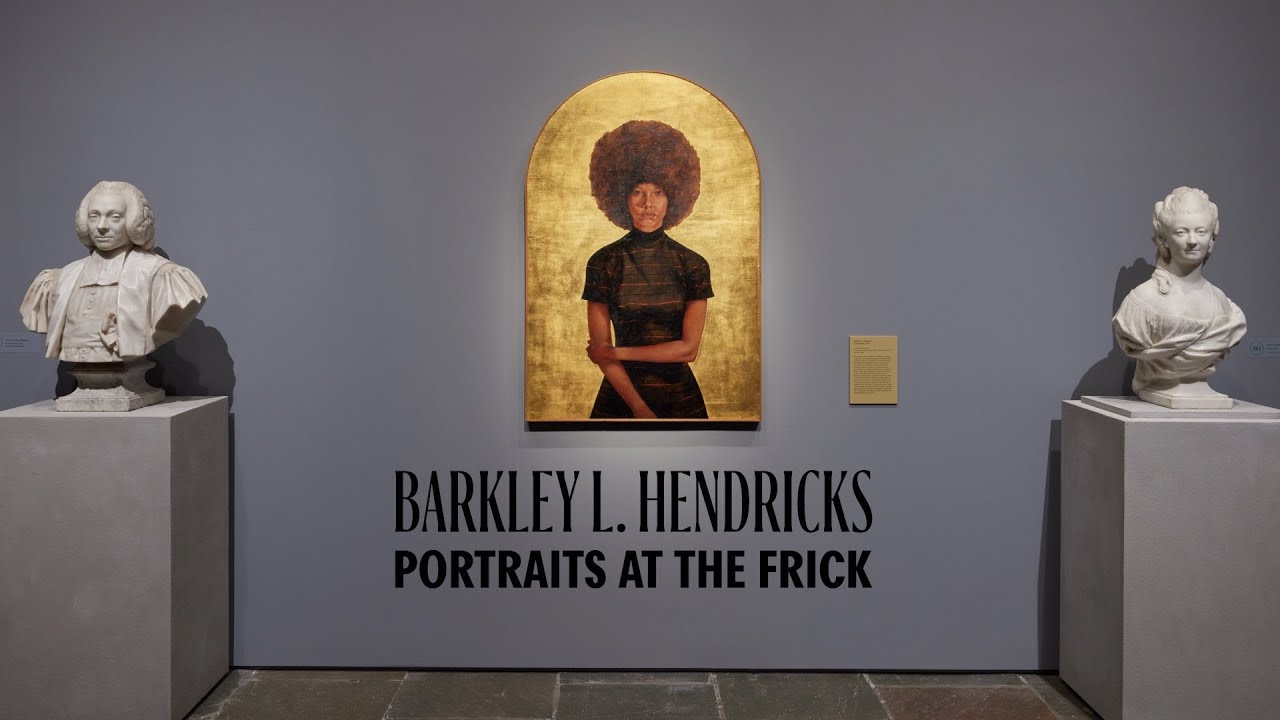

Barkley L. Hendricks: Portraits at the Frick

They say that Nipsey Hussle is your favorite rapper’s favorite rapper and the same might be said for Barkley L. Hendricks, if you swap out ‘rapper’ for artist. In the 3 rooms filled with Hendricks’ portrait work at The Frick Collection’s temporary Madison location it’s impossible not to see his influence on some of today’s biggest names. When possible, he’d ask someone to the studio to stand for him but more often, Hendricks would prowl his neighborhood, the college campus where he taught, and markets when he traveled abroad to immortalize people who caught his eye using his ‘mechanical sketchbook’ (a camera). While Hendricks’ photos were taken by him in his own lifetime, the photo-to-fine art transformation is alive in Bisa Butler who takes iconic vintage photos of Black people and quilts them into just-larger-than-life size tapestries. Hendricks’ is credited as a pioneer in capturing the luster of Black skin on canvas and it’s hard not to imagine a budding Kehinde Wiley remixing those colors on his palette (it’s possible this is mentioned in Wiley’s foreword for the catalogue.) I hope Nipsey Hussle got his roses while he was alive, but I don’t think Barkley Hendricks would have cared one way or another. The exhibit, organized by Aimee Ng and Antwuan Sargent, is careful not to exalt Barkley onto a pedestal. While all but one of the portraits in the show feature Black people (the exception is a portrait of Hendricks’s wife, who is white), the curators dissuade the reader from seeing Hendricks as a movement artist because it’s not how Hendricks saw himself. In the museum labels, Hendricks is described as anti-cultural. He preferred to study the “Old Masters” and found his inspiration in Europe rather than align with the artists of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960’s. Barkley attended the African Culture Festival FESTAC ‘77 in Lagos and even painted some of the people he saw there, but he was adamant that none of his work was political. While this revelation may sour the opinion of this pro-Black viewer, the representation in Hendricks work makes lemonade from these lemons.

There’s richness in each of Hendricks’ selected portraits and they’re separated into three sections by background color: gold, color, and white. Both Wiley and Butler share a tendency to incorporate a colorful background, though theirs are significantly more intricate. Hendricks’ attention to detail and technical mastery delivers small treats to the viewer. There are reflections of the painter or another subject in the glint of an eye or a silver earring, the jeans are “worn” (not painted) to include every crease; and the monochromatic pieces create variety through shine, the background is matte and the subject is glossy. Many of these artistic glyphs can only be viewed in person, which is all the more motivation to see the show before it ends in early January 2024. Be sure to follow along with the excellently narrated Bloomberg Connects audio guide, which gives the context Hendricks doesn’t through the voices of his students, subjects, gallerists, brokers, and friends. In the white room, Barkley uses less color, but even more intention. He explains that “in a white on white portrait, the head floats like its like flying, the ultimate freedom.” His self-portrait, entitled Slick, is in the white room and the audio guide explains that he’s being cheeky in his title and his expression. It’s clear through his work that the artist has little interest in being pinned down and defined. It’s only fair that he be granted the same liberation he lends to his subjects suspended in white.

When you’re finished, head downstairs to the woman-owned The SisterYard cafe for their exceptional coconut cold brew coffee (just try it) and decadent quiche trucked in daily from Brooklyn.