Amy Sherald: American Sublime at the Whitney

Shifting my weight from my right side to my left as I queued on Gansevoort Street just before opening time, I repeated the mission in my mind. I had exactly an hour. There would be no lallygagging, no navel gazing, no contemplative wandering. I was to get into the museum, see what needed to be seen, and catch my flight to Houston. There was no telling when I’d be back.

Art under pressure is no favorite pastime and few things in life are meant to be experienced while in sport mode, but duty called. While I’m (blessedly!) not sandwiched between caring for elders and youth, I am a daughter, and one day when I wasn’t paying very close attention my parents became old enough to (occasionally!) need my help. It’s a very ordinary thing, being present with family during a period of recovery, but it was both my first time and the front page story of my life for a full ten days. Staring at my reflection in the bathroom at my father’s house, I expected to see the impact of the moment seep out through the features of my face. I thought I’d see a version of myself that was somehow different — perhaps grizzled or wizened — but it was just the same old me, my inner life was just as sequestered as before. (As the church saying goes, Thank god I don’t look like what I’ve been through.)

The same could be said of the subject of “Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance)”. There’s very little — visually — that reveals the sum of her experiences or the current headline of her life. She’s a woman in a halfway-polka-dotted dress with a red rosette cap and her white-gloved hands grasp a palish teacup and saucer. The mottled blue background is just as tight-lipped on intel. She’s taken out of context (she could be floating for all we know) and her face tells us even less. There is no furrowed brow, no puzzle in the expression, no eyes that follow you around the gallery. Her expression, smooth and at ease, is intentional on the part of the painter-storyteller, Amy Sherald, who aims to capture “everyday Black Americans, compelling in their individuality and extraordinary in their ordinariness.”

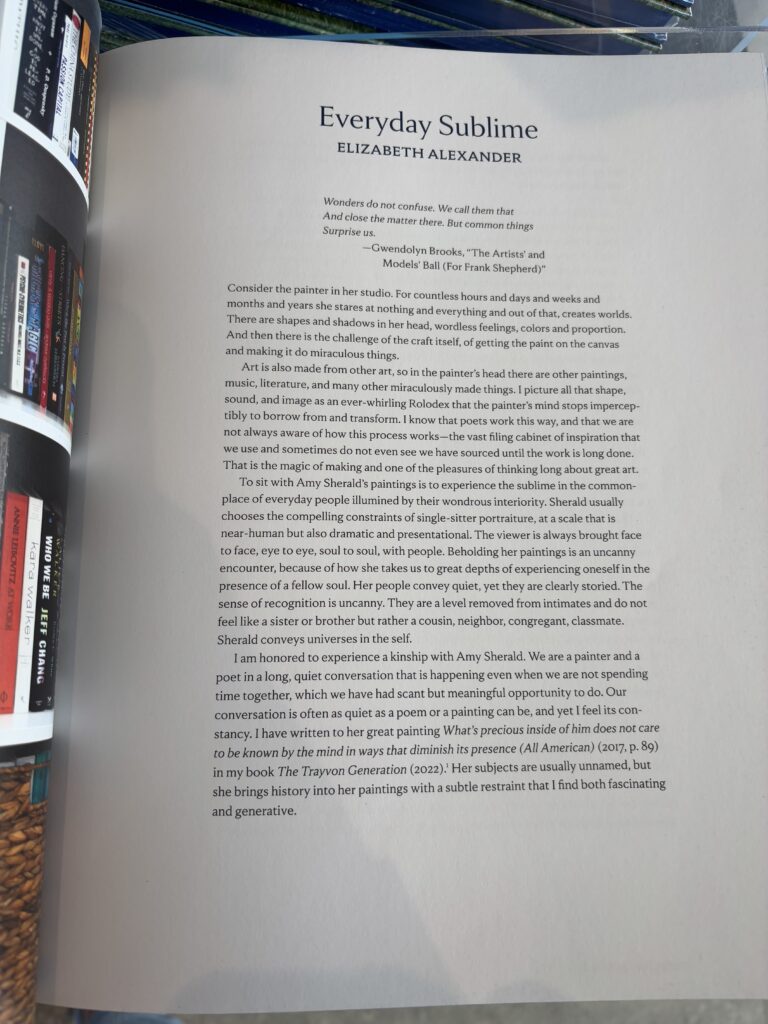

Sherald is telling us a story but she refuses to confine her narrative to the quadrilateral dimensions of a canvas. Her intention perfuses through carefully chosen titles, which are often selected from the canon of Black women writers (which includes Gwendolyn Brooks, Toni Morrison, Zora Neale Hurston). Even the title of the exhibition, American Sublime, is repurposed from Elizabeth Alexander’s 2005 poetry collection of the same name. While the actual exhibition is light on language, there are excellent essays and analysis in the exhibition’s accompanying book, one of which by Alexander explains the kinship between her work and Sherald’s. (As we teeter on the brink of a recession it’s a let down that the $30 admission fee doesn’t include access to very much depth of understanding; the good stuff is tucked into the book and costs an additional $45.) Alexander alludes to the idea that a list of the works in this exhibit would deliver its own sort of free verse poem.

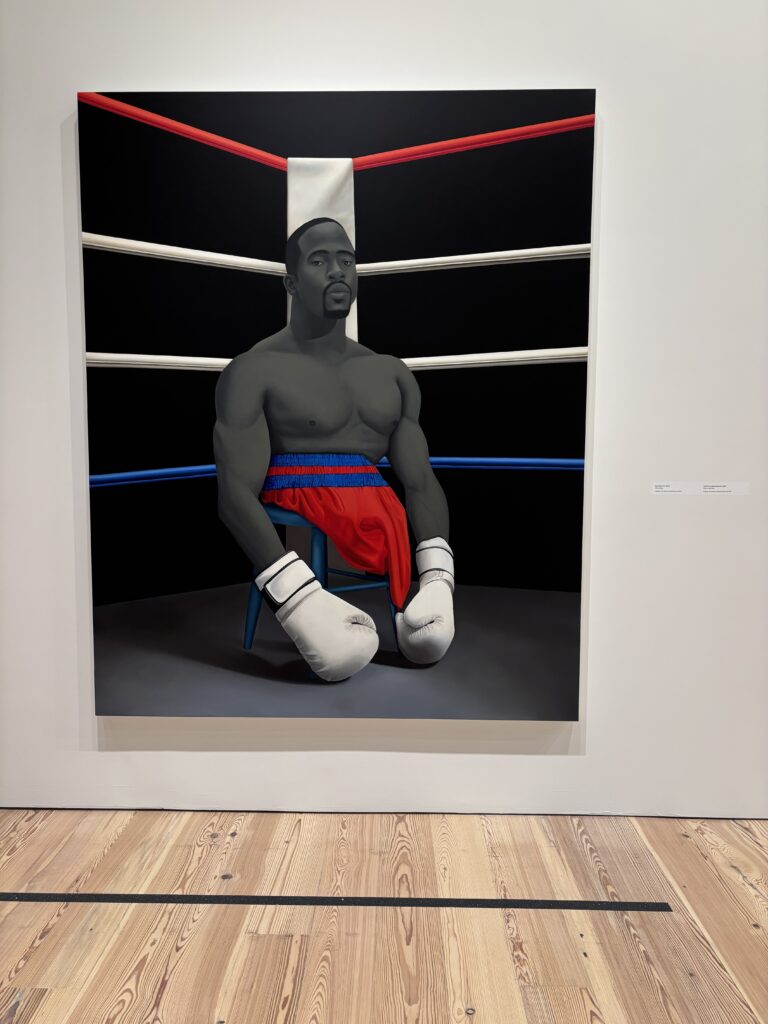

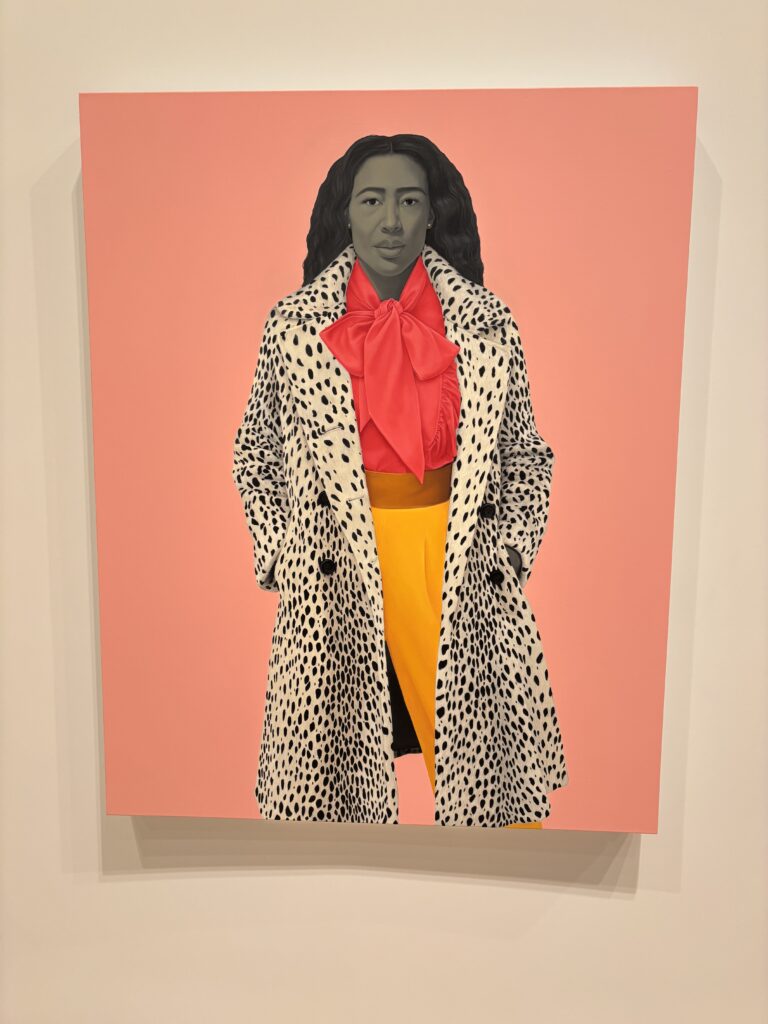

If titles and poetry are not your thing and you’re set on intuiting the meaning of the show from images only, then the true story of American Sublime is in the details. Ordinary ones: the girder of a bridge, a picket fence, a superhero t-shirt, an engagement ring, boxing gloves, painted fingernails. These details are simple but never coincidental. Like many portraitists, Sherald sees photography as “the beginning of the work”. The Art21 film “Everyday Icons” that plays in the screening room shows her finding models, dressing them precisely, posing them intentionally, and snapping their photo in front of the exact same color background she plans to use on the canvas. I found this method surprising: it’s common to ‘sketch’ a portrait using a photo, but it’s less common to capture that photo exactly as it will appear when it’s painted. For example, painter Barkley Hendricks would photograph models in his studio wearing whatever clothes they had on that day and Hendricks would redress them to his liking in his work to emphasize what he thought most important. (I specifically recall listening to the audio guide during my visit to the Hendricks show at the Frick Madison in 2023 and hearing the model for “Blood (Donald Formey)”, who Hendricks met on campus, explain that he’d been wearing something different.) In other words, Hendricks’s paintings look different than the source photos, while Sherald’s paintings are near exact recreations of the photos she’s posed. The one consistent difference between her photos and her paintings is, for many, the most noticeable aspect of her style. The characteristic that allows you to spot a Sherald with ease? Grisaille.

Sherald paints us gray, to “de-emphasize… focus on her subjects’ race and instead draw attention to their individuality and interiority”, but this does not render us monochromatic, monolithic, or attempt an erasure. Even in their 50 shades of gray, the subjects are undeniably Black. It’s evidenced by their hair, their features, their outfits. They seem a heartbeat away from seeing you see them; if they could move they’d surely reciprocate the universal Black nod. There is a certain in-group understanding that comes naturally to Sherald and makes me feel attended to as a member of the Black viewing public. Her “broad [view of] American Realism” was informed by her time at Clark Atlanta University (an HBCU) and her ongoing communion in Black spaces. As Sherald has refined her style, she’s become even more ambitious and clear in her message. There’s less room for misinterpretation of her goal. In “Trans Forming Liberty” a non-binary femme in a pink wig stands barefoot with a torch à la Lady Liberty. In “For love, and for country” she collaborates with models to queer the famed kiss from the 1945 photo from the World War II ticker tape parade. (It’s worth noting that, Greta Friedman, the woman in the original photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt was kissed without her consent. CNN explains, “Friedman reflected in 2005 that the encounter “wasn’t a romantic event,” adding: “It wasn’t my choice to be kissed. The guy just came over and kissed or grabbed (me).”) While the potential for pushback from the closed-minded and bigoted is strong, these works read as gleeful reimaginings and contrast her more somber work. Sherald’s painting “Breonna Taylor” shows a goddess at peace in a version of her life where the engagement ring her boyfriend purchased for her has actually made it to her hand. All three of these paintings represent what could be if we’d be bold enough to love one another, what could have been if we weren’t a nation obsessed with violence.

The tragic magnetism of the Taylor painting contends with the historical significance of the official Obama portrait and either (or both) could be seen as the show’s seminal work. Your preference between the two may trace back to the timing of your first Sherald encounter. I had no knowledge of her before First Lady Obama’s portrait (forgive me, there was no Black Star Reviews back then!) but suddenly I knew this artist by name and common critique. Discussions abounded on why Mrs. Obama was gray, whether her face shape was accurately captured, and how the lack of color made it pale in comparison to Kehinde Wiley’s technicolor portrait of her husband, President Barack Obama. These questions seem valid if you have no understanding of Sherald’s style, but Mrs. Obama commissioned Sherald for a reason and is entitled to be seen through Sherald’s eyes. Standing in front of the portrait could clarify the rationale. When I stood at an arm’s distance, just behind the black tape on the floor, I could see the story-telling details for which Sherald is famous in ways that never translated on a palm-sized phone screen or a glossy magazine. Here without an intermediary filter, I could see the flexed muscles in Mrs. Obama’s jaw, that one of her eyes is slightly smaller, the blunted roots of her braids (she didn’t opt for knotless), her manicured fingernails, the soft glam hallmark of highlighter swept beneath the brow bone. Not to sound all Gayle King about seeing something many haven’t, but just this once I ask that you withhold your judgement until you’ve stood in front of it for yourself.

I want you to see Sherald’s intentions with the same eyes that she uses to see us. Through her work Sherald expresses understated beauty, unrealized potential and slowly dissolves the masks we carry to be seen and accepted as American. This assertion that Americanness is a state of being and not one that must be earned through assimilation is heroic in a political moment when no one is safe from deportation and imprisonment, not even those born on the soil of these United States.

I made it in and out of Amy Sherald’s American Sublime within my allowed hour, and even went back through to grab footage for TikTok and double check that I’d caught all of the labels. I’d been worried that I’d run out of time, that I’d be overwhelmed trying to take it all in, that I wouldn’t feel prepared to create my write-up for this living archive. As it turned out, the show felt restrained, a word Alexander also uses to describe the collection near the beginning of her Everyday Sublime essay. Alexander writes, “[Sherald’s] subjects are usually unnamed, but she brings history into her painting with a subtle restraint that I find both fascinating and generative.” The simplicity of the collection allows for the viewer to spend time with each face — each everyday American — to glean who they might be and what might be of import to them. Amy Sherald has seen my face, though briefly. We shared an elevator at the Apollo in Harlem. I told her I followed her work and that was how I’d recognized her. She responded that I was able to recognize her face because it looked like my own. I was too stunned and flattered to respond with a quip and wished her a good evening, but I thought about that exchange during my hour at the Whitney.

Later that day when I arrived in Houston, my face was one of the first my father saw after his ocular surgery. As his eyes heal, he might see me blurry, or clear, or with a shadow but at least he’s not relegated to recalling me from memory. It’s been a week since the operation and I’m relieved when he can read me the answers from Family Feud. I’m grateful when he can tell me what color lipstick I have on. Small things, details. When I view the world through my father’s eyes or through Ms. Sherald’s, it’s clear to see how what is ordinary can also be compelling, can also be sublime.

Amy Sherald: American Sublime will be on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art from April 9th, 2025 to August 10, 2025. Museum admission is free on Friday nights and Second Sundays, otherwise, general admission for adults (over the age of 25) is $30.

- Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance) (2014)

- Trans Forming Liberty (2024)

- For love, and for country (2022)

- Breonna Taylor (2020)

- American Grit (2024)

- As Soft as She Is… (2022)

- A Midsummer Afternoon Dream (2021)

- As American As Apple Pie (2020)

- Excerpt from Elizabeth Alexander’s essay, “Everyday Sublime”