Apollo’s [at] the Intersection: Festival of Arts and Ideas

There are few venues more iconic than the Apollo Theater, but it’s not like it has many rivals still standing uptown. Next door, the Victoria Theater has been refashioned into a Renaissance Hotel, only the facade remains of the building in Washington Heights where Malcolm X was murdered, the Lenox Lounge is a Wells Fargo bank, and the Cotton Club only opens every quarter moon. The Apollo will never not be a part of musical history and it’s making a valiant effort to maintain its relevant in the here and now. After all, even one million Spotify streams won’t feel as fulfilling as evading the Sandman and receiving a standing ovation at Amateur Night.

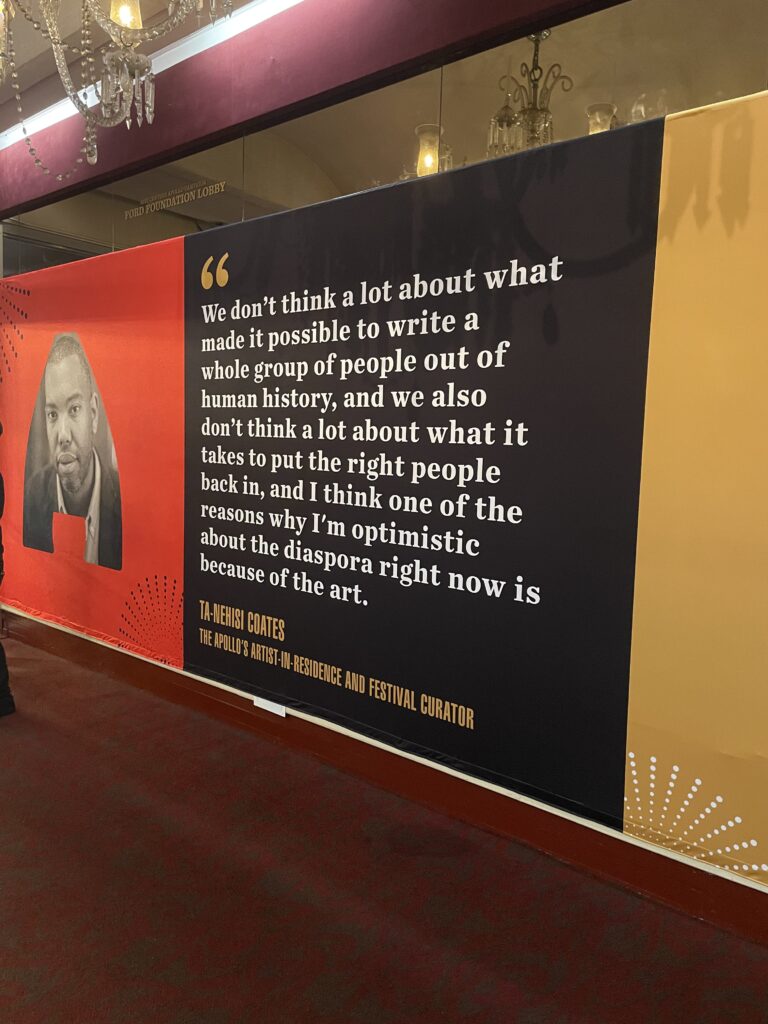

Author, public intellectual, and current Apollo Artist-in-Residence Ta-Nehisi Coates curated a festival of arts and ideas that convened A-list Black creatives for a conversation on where we go from here. A three-day pass covered admission on Friday, Saturday and Sunday and Day One was dedicated to screening three works by Barry Jenkins, who would be in conversation with Ta-Nehisi the following day.

Three movies is probably one too many to sit through in a dark theater mid-day, even if you spend the 15 minute breaks between each film on the sidewalk seeking sunlight. However, it was a unique opportunity to see the development of an artist from their first work to their most celebrated.

Medicine for Melancholy (2008), Jenkins’ first feature-length film as a writer and director, features a young Wyatt Cenac and the long pauses, facial close-ups, carefree frolicking, and intentionally ‘greige’ coloring common to indie/quasi-indie films of the time [Frances Ha (2012), (500) Days of Summer (2009)].

The next film, If Beale Street Could Talk (2018), adapted from the Baldwin novel is actually Jenkins’ most recent as well as his most beautiful. In this film the facial close-ups and setting shots are perfectly timed — any moments spent lingering on a face, or a city block, or a piece of wood are intentional — and carve out space for the viewer to feel the plight of Tish, Fonny, and everyone else dragged into tribulation with them. The casting buttresses the beauty: Regina King as an understanding and unyielding mother, Colman Domingo as a hustling and honest father, Aujunae Ellis as a holier-than-thou deaconess deluded by righteousness, Stephan James as the perfect mix of gentle, masculine and most of all, innocent. One could argue that Baldwin may have done most of the heavy lifting in writing the story for Beale Street, but Jenkins makes us see the story in images the book doesn’t describe: a mother in a mirror, a haunted look in the eyes of childhood friend, a white cop with a razor sharp jawline and a pointed vendetta, and a son made in the spitting image of his father who has always worn a number on his chest.

The finale for the screening was Jenkins’ greatest achievement in his career (so far), Moonlight (2016). Based on an unpublished play by fellow Miami native, Tarell Alvin McCraney, it went on to bring awards and attention to the story and cast. Jenkins used his strengths — stretches of silence, focused shots of facial expressions and reactions without dialogue (Little Chiron barely has 5 lines in Part 1) — to create moments of intimacy that preserve the characters’ humanity in ways that erase any shame you’d feel for ‘looking in’. But there’s something missing.

None of the films in the screening have an ending. In Medicine for Melancholy, the female lead looks up one last time and bikes away while her lover is still sleeping. In Beale Street, Fonny and Tish spend their prison visit dreaming about a release date that feels too far away to ever be real. These endings seem finite in comparison to the end of Jenkins’ trophy film. In Moonlight, two teenage lovers lost to time find their way back as adults. They catch up across a vinyl table in a diner and Kevin addresses Black by his given name to ask the closing question of the film, “Who is you, Chiron?” From what we’ve seen of his life as Black in Part 3, he lives in a modest apartment in Georgia, sells drugs, enforces his power, and tries to forgive his mother for her transgressions while she was addicted. Chiron’s redemption and acceptance in response to Kevin’s question are, much like the desires of everyone in his early life, projected onto him. Can we really know enough about Chiron’s desires and emotions to intuit his answer? Life happens to Chiron until he decides to reinvent; and in doing so, he becomes a version of a man who’s untouchable in street culture and matters of the heart.

To sum Jenkins up as “a talented filmmaker” is narrow. His ability to capture attraction, love, and tenderness and how those sentiments grow across a story makes him a singular talent. It will be thrilling to see if his next project will allow its characters to speak for themselves, hold a mirror up for the audience, or some balance of the two. In any case, his attention to aesthetic makes certain that future films will be cinematically arresting.