“The Great Privation…” at Soho Rep

In the novel Ring Shout by P. Djèlí Clark, the protagonist is part of a militant league to protect the Black people of Georgia from the Ku Klux Klan. In the world of the story, there are two truths: the Klan are human participants in the hate group and the Ku Kluxes are otherworldly monsters hiding in plain sight by concealing their pointed heads and razored-edged teeth under those stark white hoods. Our hero, Maryse Boudreaux, is one of the few people who can see who’s who and she’s trying to prevent a screening of Birth of a Nation from unleashing the full power of the Ku Kluxes. At her wit’s end, she seeks help from an even darker force and enters into the flesh of a tree to make a request of another mystical creature, ones that cut things up and eat their pain. They’re called the Night Doctors. Maryse lures the doctors by telling them where they can get all the pain and hatred they care to eat and cuts a deal for these demons to take a few Ku Kluxes off her hands. Maryse knows this is a risky deal because in the world of the story there are two truths: there are demon Night Doctors who live in another dimension accessed through a bone-pale tree and there are the human Night Doctors children are warned against in songs and sayings. Just like there are humans in the KKK hate group, Night Doctors are real. In Maryse’s world as in ours, Black people were taught her to watch out for those who’d creep through graveyards, hospitals, dark streets, and even in your window to haul you off as a human sacrifice to the Gods of Medicine. I’m not sure what’s stranger or more grotesque here, the truth or fiction.

You can imagine my surprise when shortly after returning the novel to the Countee Cullen branch of the library, I sat in the third row of a play where a white man with a shovel arrived in a cemetery with no cloak, no beguilement, and no shame at all. I added another type of Night Doctor to my watch out list: 1) mystical ones from a wholly separate plane, 2) historical ones who snuck around stealing bodies, and 3) the ones who didn’t sneak because they didn’t think a dead Black body belonged to anyone besides ‘scientific progress’. The last kind is the version we see in Nia Akilah Robinson’s The Great Privation (How to flip ten cents into a dollar) which began previews in late February.

The play is described by the Soho Rep team as a dark comedy and I think the use of the word ‘dark’ undersells it. The show begins in an 1832 Philadelphia graveyard, where a mother and daughter stand vigil at the grave of their patriarch long enough for his spirit to return home while his body is still intact. According to the mother, it takes 72 hours for the spirit of a loved one to fly across the Atlantic Ocean back to Africa, the homeland of the father’s ancestors. The two sit in mourning and on watch. They’ve paid for a premium grave site by a tree and it isn’t long before a white man with a shovel arrives asking them when they’ll be gone. Both sides are bound to the same timeline, the body can’t be harmed or touched for 72 hours to make it to Africa and the body must be brought to the lab within 72 hours in order to be useful for research. The mother is determined to wait it out and tells him so. Later, a Black man arrives with a shovel and a missive, dig up the body and return it to his employer before the clock runs out.

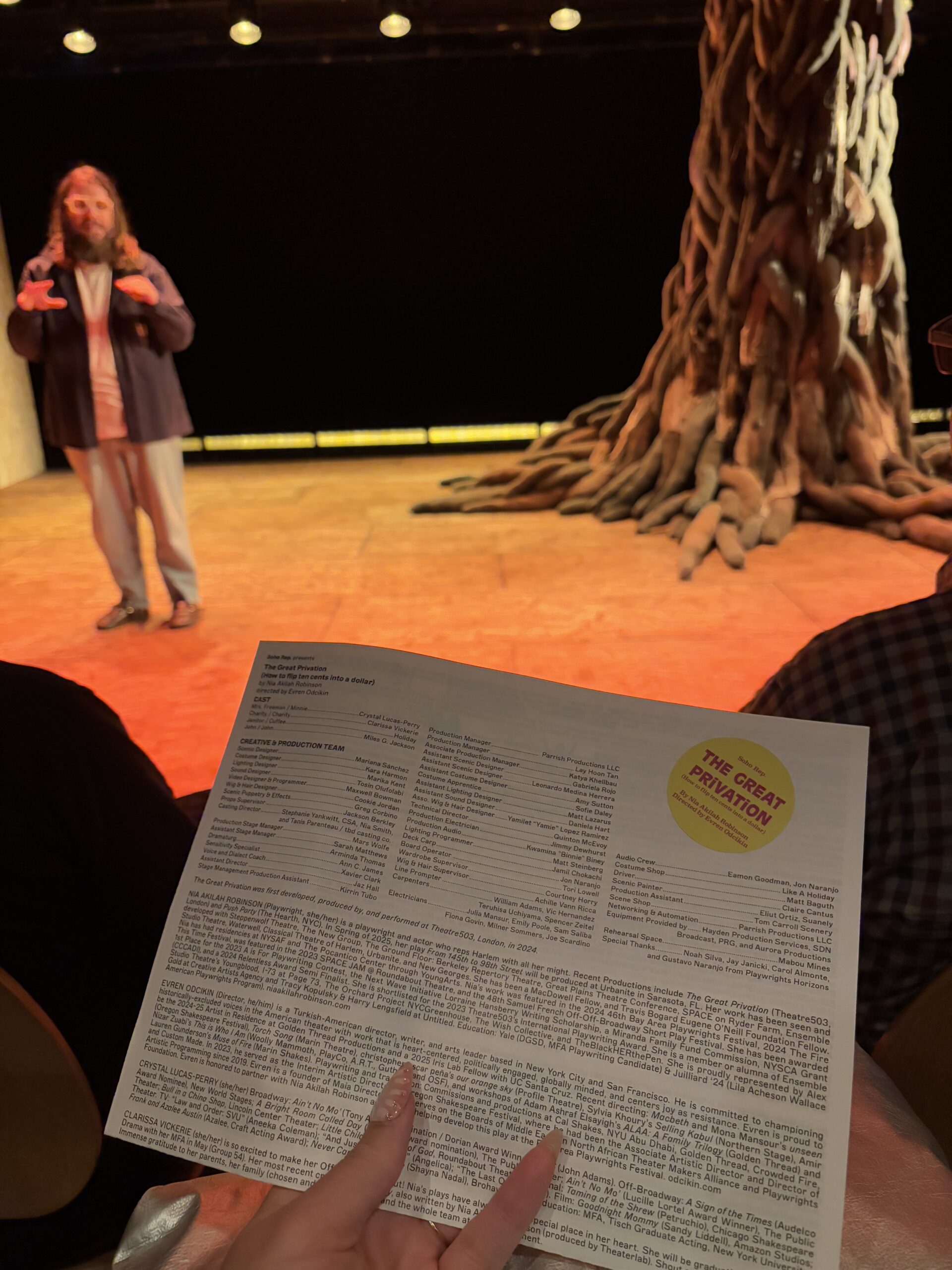

On stage there’s a literal clock, just left of a large tree that looks like the kind you can live inside of. The clock starts at 72 hours and counts down, but it also counts up and stops altogether when we fly into the future: same place, different time.

In the present day, the mother, Minnie, and the daughter, Charity, are their own descendants and working at a summer camp in Philadelphia built on the former site of an African church and graveyard. The white man, John, is a fellow camp counselor, and the Black man, Cuffee, is a camp director. The tables appear to have turned, but not very far. The white counselor John, despite having less experience and fewer years with the company, makes more per hour than Minnie, the Black mom. Dynamics are revealed like peeling tree bark, a few layers at a time. John is sour that Cuffee’s behaving differently after being promoted above him, especially because they used to sleep together. In an effort to win the women over in his campaign against Cuffee, John tells them about the strange hauntings at camp during nightfall. When the two women join him later that evening with flashlights, the time periods collide in the characters’ bodies. John is both John the fun, queer camp counselor and John, the white medical student who chops up dead Blacks for research. In the past, Charity is a hard-headed daughter who wants to teach her mother to read and in the present, Charity is a hard-headed daughter who wants her mom to understand and support her participation in student activism. From there, we jump back and forth in time, characters are spirited in and out of their bodies, and remains are taken and returned in various ways.

Everyone pulls their weight in this modest cast of four. Cuffee, played by Holiday, grapples with both sides of being a go-between which often sacrifices Black acceptance for white trust. He shines in a cameo as Black Jesus, complete with glitter Afro. John, played by Miles G. Jackson, seemed to have met every queer white camp counselor I’d ever worked with (there have been many) and bottled the ways they perform allyship even while speaking over you. They’ll spend every lunch break empathizing with your salary woes and never mention that they out-earn you. It feels only right to mention Crystal Lucas-Perry and Clarissa Vickerie in the same breath, since their chemistry and ability to play off of each other sold the frustrating mother-daughter dynamic that drives the conflict in the story. I don’t want to see the show without Lucas-Perry, I don’t want to see the show without Vickerie. They’re powerful together and I’d like them to stay that way. Without saying too much, I will also acknowledge the clever use of special effects to revive and bring peace to the dead. (I’d been dreaming of resting my head on the soft trunk of the tree, which resembled overstuffed legs of pantyhose woven over each other, until it came to life!)

Admittedly, I’m not fully certain of how the title fits into the narrative, but I’ll share my working interpretation. This story isn’t specific to a site in Philadelphia, New Yorkers walk, bike, run and picnic over the former homes of Black people in Seneca Village. The African Burial Ground was ‘discovered’ in 1991 during the construction of a federal office building downtown. Due to incessant letter writing and organizing by Black activists, the site is now a National Monument. The onsite museum has a timeline of how developers reckoned with the remains of more than 15,000 Africans who had been buried on the land going all the way back to the 1630s. Nona Faustine, who sadly passed away this week at age 48, created the phenomenal photo series White Shoes and included a photo of this sacred site in her collection. In “Protection, African Burial Ground Monument, NYC” (2021) [view here] she’s in a gold shawl, kneeling in prayer and offering us rest. The play asks, “How do you bear it?” and responds that every Black person has their own answer. How do we bear developers building on our graves, and thieves stealing our bodies, and companies exploiting our work, and nations erasing our history? Sure, we have answers but we lie to ourselves when we think that Black people are the only ones who pay the price of these truths.

Present-day Charity reclaims her power through civil disobedience at her private Upper East Side school. Cuffee longs for community to fend off the ‘cold’ pressure of being the first openly queer and Black camp director. John, upon finding out his ancestor’s role in the whole historical saga, wholly disappears — he can’t face his coworkers, his boss, or his campers. Real-life Black people, like the characters in the play (past and present), don’t always get to choose how we’d like to bear it. Still, we persist, we resist, we exist. But the way forward is not only up to us.

Since I enjoy writing reviews, I hope it doesn’t surprise you that I like to read those written by others and after finishing Ring Shout I sought out additional perspectives on the book. I came across one by Matthew Teusch entitled “The Monsters Within in P. Djèlí Clark’s Ring Shout”.

Teusch, a white professor of African American, Southern, and American literature at Piedmont University in Georgia, focuses his review on two extremely minor white characters in the book and how they narrowly avoid becoming consumed by hate and are instead haunted by the true faces of the demons behind the hoods. Teusch compares this moment of awakening to touchpoints in his own life and invokes a letter by Lillian E. Smith to the Blue Ridge Conference in 1944. Her letter is a follow-up to her appearance at the conference, which from the tone of the letter, was not well-received. In her two-page typewritten dispatch she warns her fellow white Southerners to see the “racial problem as the ‘white man’s problem’”. She writes on to say that “feelings of superiority breed paranoia, and I know that such feelings, carried to an extreme, will make people mentally ill. I am as afraid of being infected by white arrogance as I would be of syphilitic infection. The whole thing simmers down to this: if you value sanity, you cannot afford to hate or feel that others are “beneath” you. Hate destroys us and those around us.”

It’s true that every Black person has their answer when asked, “How do you bear it?” but this does not absolve everyone else from finding an answer of their own. While you flip your dimes to dollars, hatred exacts its own toll from the inside out. As John finds out in the play, ‘white arrogance’ is a sickening inheritance even when it comes with economic comfort. Whether white people deal with their hate in this generation or continue to postpone, the hate will come home to roost. When it gets too rough out here, send my soul to Africa.

The Great Privation (How to flip ten cents into a dollar) was written by Nia Akilah Robinson, directed by Evren Odcikin, and produced by SoHo Rep. This play will run from February 26 until March 27 at Peter Jay Sharp Theater at Playwrights Horizons. Tickets are $35 and on select Sundays, 99¢.

I attended the third preview of this show with 11 friends as part of the Black Star Reviews One Year Anniversary celebration.

- with the playwright, Nia Akilah Robinson