Black Zine Fair 2025

The annual Black Zine Fair in Brooklyn celebrates Black expression by connecting small press printmakers, independent publishers, and handmade zines with the people who 🖤 them.

I knew I was within spitting distance of the venue when a lanky figure with waist-length rainbow-colored locs and oversized headphones rolled past me on a longboard. There are a handful of American cities (*cough* Austin, *ahem* Portland) that like to think they’re in competition for being the “weirdest” but Brooklyn does it better, with more people, and in a smaller patch of square miles.

The Black Zine Fair, organized by a micro-press called Sojourners for Justice, took place this Saturday in Brooklyn, a few blocks east of the Gowanus Canal. Vendors set up an inner and outer ring of tables in the airy and industrial 3rd floor of Powerhouse Arts, an organization that acquired the remaining portion of a 117-year old red-brick building and reimagined the power station as a “fabrication facility and multi-use arts center.”

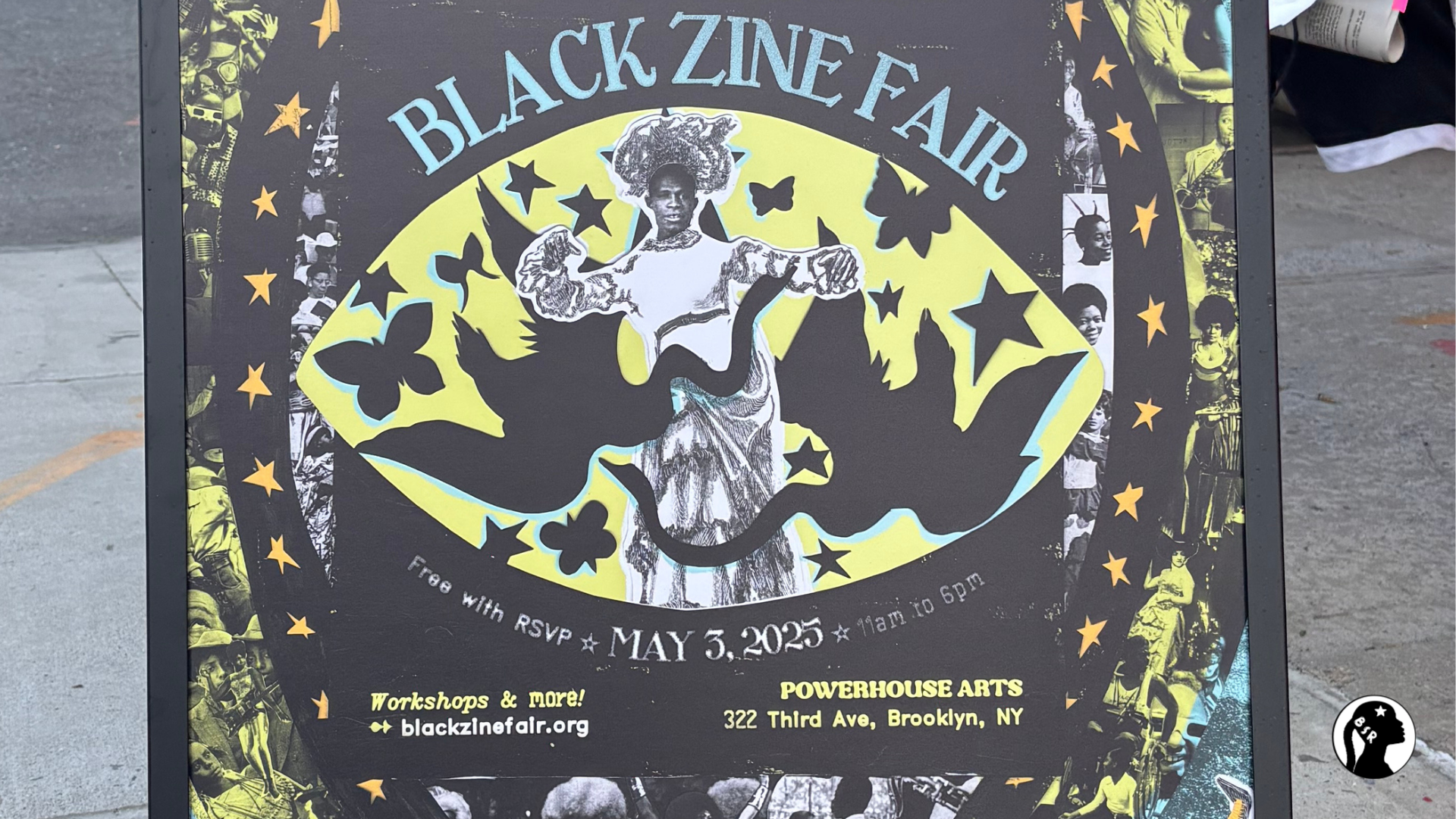

Tables were decorated and designed with individual flair and while zines were the focus, some vendors also sold postcards, wall art, chapbooks, stationery, and intricately designed mesh crewnecks ($155) that echoed the same tattoo-decoupage-fanfare/carnival aesthetic as the event’s branding and posters.

In the center of the poster is an image of a man often thought to be (but is not) William Dorsey Swann. (We dedicated the Cats: The Jellicle Ball Youtube episode review in his honor!) Swann was born into slavery in Maryland a few years before the Emancipation Proclamation; by adulthood he was free and living in Washington, D.C. His name was in the paper more than a few times for his repeated arrests. Swann hosted a series of drag balls and each time there was a raid, he made the news. When he was eventually convicted for “keeping a disorderly house” he wrote to President Grover Cleveland to request a pardon. While President Cleveland did not see fit to pardon Swann from his 10-month prison sentence, Swann’s letter-writing and news-making is the reason he hasn’t been lost to history. A number of articles allude to Swann’s outrageous outfits and pioneering drag style, which has led casual researchers to trust the first image result that appears when you search his name. The individual that appears is not Swann, but the tiered gown, fashionable hat, and playful pose evoke a freedom that Swann might have felt; not only a freedom from slavery, but from gender norms, and societal expectations, too. It’s fitting that Swann’s stand-in is featured in the literature for the Black Zine Fair, since zines — small, self-published booklets — are certified queer-core.

The first zine I picked up inside was titled, “What Are Zines?” Even though it only had four pages, it answered a few of my questions. What are zines and why are people still making them in the Internet era? It turns out the small booklets are an efficient way to disseminate information, especially the sensitive kind. It’s an ideal medium for a message that you deem worthy of sharing, but that you don’t want going viral on the Internet. There’s an intimacy in the preparation as well since someone designed, folded and taped this booklet by hand. Many of the zines — priced between $1 and $5 — were deeply personal, pages of erotica, previously undisclosed trauma, or cute, candid selfies. These were not the zines I had expected.

I know from my organizing days that zines were/are a way to spread information — locations of food banks, resources for seeking mutual aid, numbers for clinics that will test you free of charge, what to do or say when you’re approached by law enforcement (especially helpful now in the ICE-age) — and in my experience these were always given freely. I was kicking myself for not taking the time to visit the Brooklyn Museum’s 2023-2024 exhibition Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines during my back-to-back visits to see Spike Lee: Creative Sources and Africa Fashion but from the outside and on the advertisements, the Zine show didn’t seem ‘Black’. The Fair acknowledges this representation issue in the FAQ section of its website, “Despite the rich influence Black people have had on publishing, there aren’t enough Black exhibitors at publishing events.” But perhaps if I had popped in to the museum show, I wouldn’t have felt completely out of my depth at the fair.

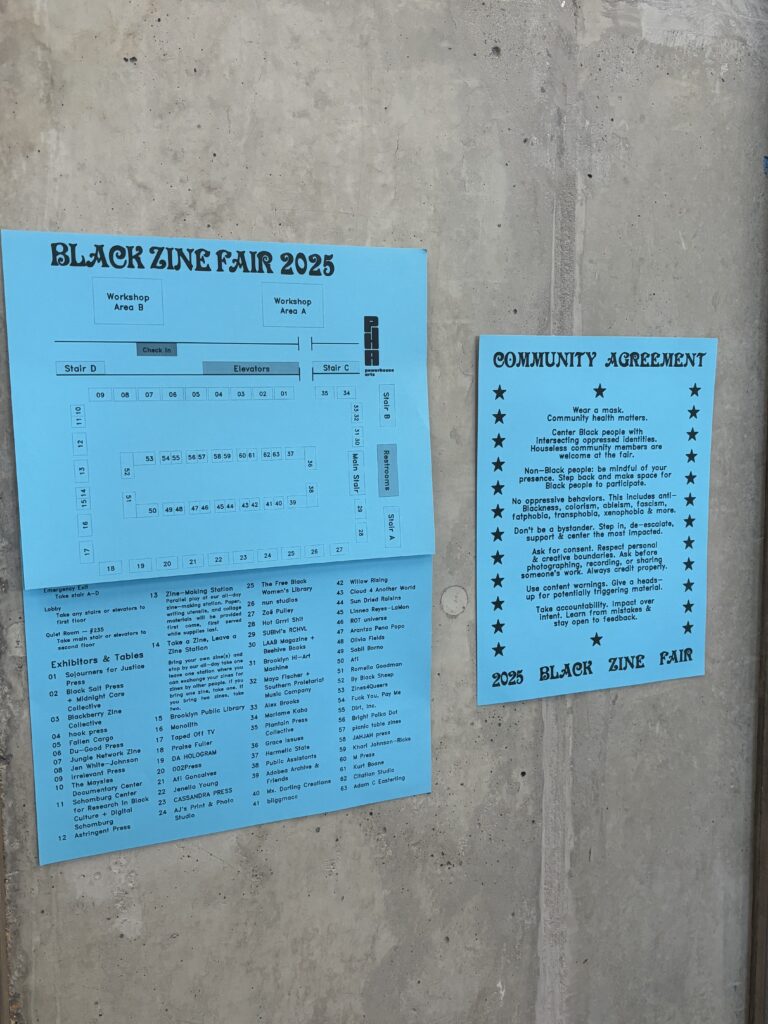

It’s not that I had a bad time at the Black Zine Fair, but more so, that I felt twenty-one steps behind. The fair was intentional about creating a safe space; a list of 8 community agreements was printed on bright blue paper and posted near the elevators. The first, “Wear a mask. Community health matters,” meant that I was emotionally transported to 2020-2021 when I would teach a full-day of school with a mask on, unsure if I’d lose a student, a coworker, or my own life to the virus. (In order to to be an ally for immunocomprised folks I’m going to have to unpack what masking does to my psyche.) The second agreement, “Center Black people with intersecting oppressed identities. Houseless community members are welcome at the fair,” had me overly vigilant about how much space I was taking up as an able-bodied, cishet-presenting person with socio-economic stability. I felt nervous knowing very little about zines and I found it hard to discern who might be willing to remediate for me since the mask blocked exhales and facial expressions alike. Who was smiling and inviting me to their booth? Who was feeling upset that I’d come by and leafed through a zine without making a purchase? Who was overthinking the experience entirely and edging ever closer to a panic attack? It’s hard to tell when eyes are the only visual information.

I didn’t stay too long or buy any zines. On my way out, I reflected on the irony. I feel fully entitled in places like The Met or Carnegie Hall, but I’d crumpled like an aluminum can over photocopied booklets in a warehouse. I was out on the sidewalk taking a photo for this website when I heard someone call my name. It was Daija, asking if I’d enjoyed myself. I told her the truth — that I’d felt overwhelmed and confused. Despite her surprise, she gave me the crash course I’d been looking for while we walked to the train. She handed me some of the zines she’d purchased or swapped and she told me what had drawn her to them. Outside without a mask, I could see her smile when I asked questions and when I admitted my own ignorance.

I’ll be back next year when the Black Zine Fair returns and there are some things I’d like to learn and do in the meantime. I want to make a zine I can bring to swap and I want to reshape my experience in the space. I want to feel as confident as the rainbow loc’d longboarder and the Swann stand-in: effortlessly me and free.

blacklove 🖤 and starlight 🌟

The Black Zine Fair is an annual event produced by Sojourners for Truth Press. The fair is free to attend, but donations are welcome and requested. To get updates about the 2026 Black Zine Fair, visit the website. From there, you can follow them on Instagram or join their mailing list.

- The Powerhouse Arts center is in Gowanus, Brooklyn and used to be a power station.

- The poster for the Black Zine Fair features a tattoo-decoupage-fanfare/carnival aesthetic. The man in the center is an early 20th Century drag performer.

- The Black Zine Fair was on the third floor of Powerhouse Arts, which used to be a power station.

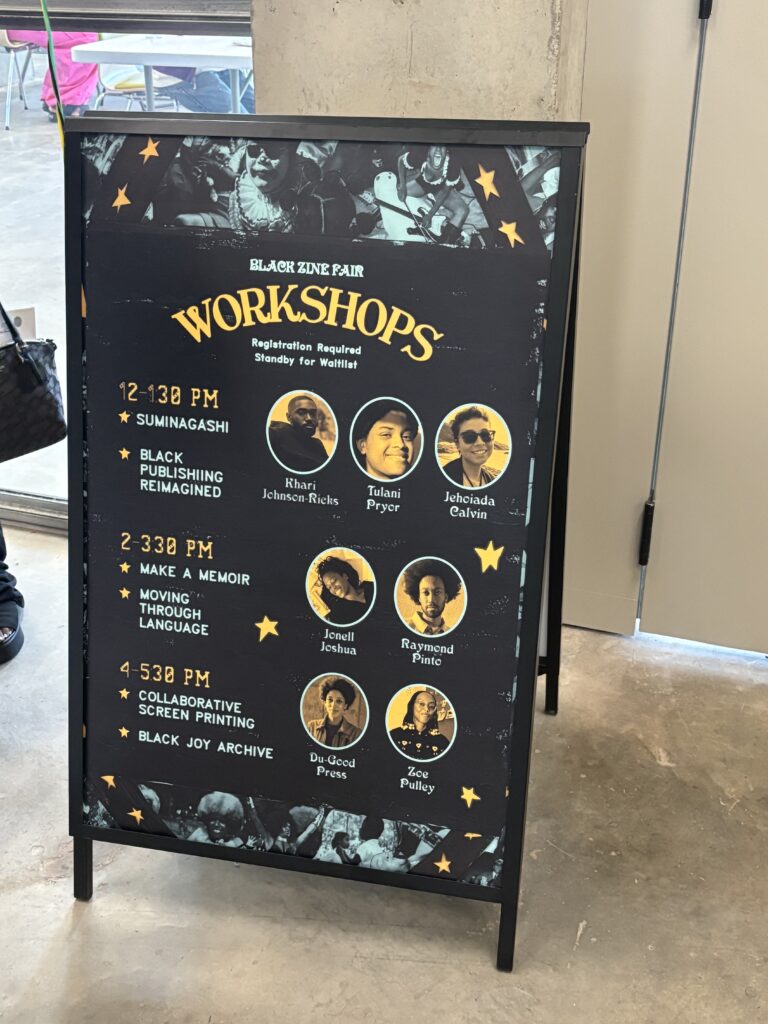

- There were workshops and supplies for amateur and pro Zine makers.

- There were 8 community agreements at the Black Zine Fair printed on blue paper and posted near the elevators.

- Powerhouse Arts is in Gowanus, Brooklyn.