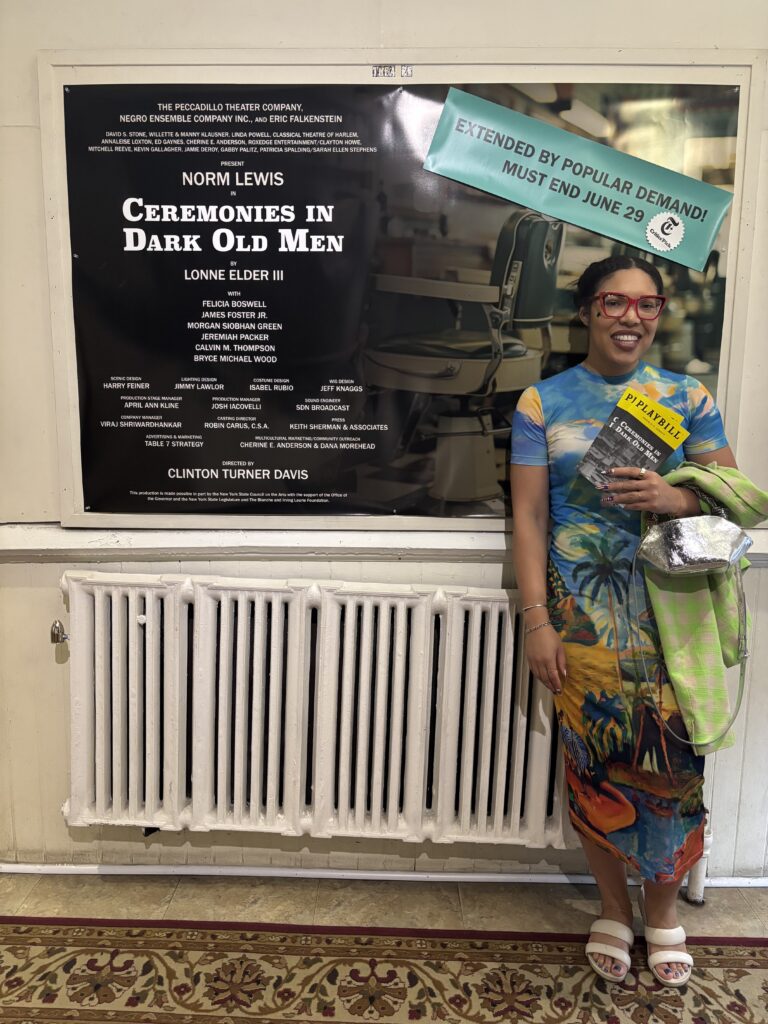

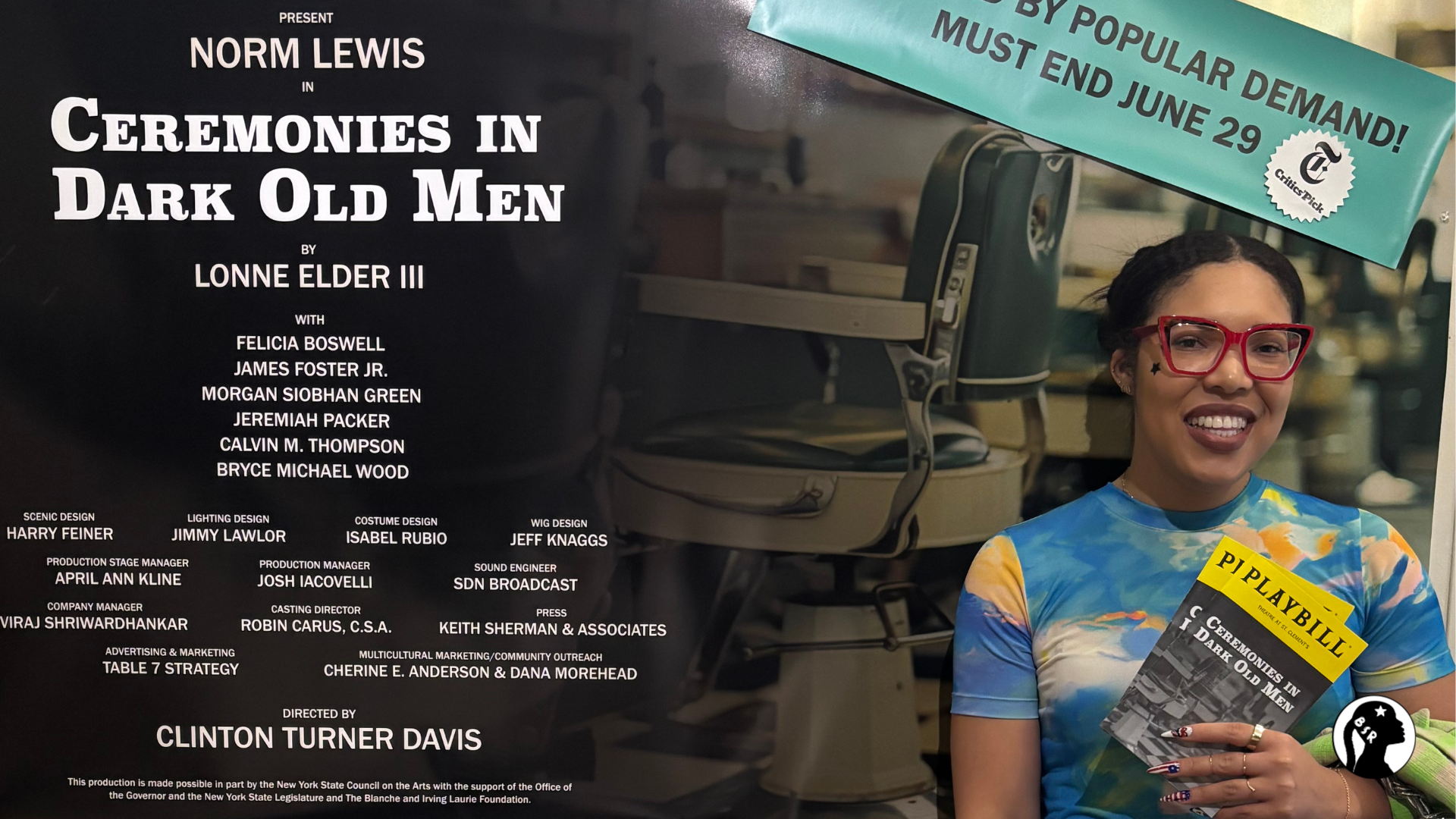

‘Ceremonies In Dark Old Men’ starring Norm Lewis

The 1969 play James Baldwin called “the most truthful play I’ve seen in a long time” proves that the ‘male loneliness epidemic’ is a new-fangled name for a chronic condition.

Not that I’d ever profess any oracular abilities, but I’m certain I saw the “male loneliness epidemic” coming before it ever reached headlines. I’d been struck by a triple punch of let-downs — fictional, romantic, and familial — in short succession and I suspected it wasn’t a coincidence that I was feeling abandoned and threatened.

The threat originated with a solo trip to the theater in 2022. I finally pulled the trigger on a ticket to see Wendell Pierce in Death of a Salesman, after grimacing at the prices for weeks. Because I was mostly there to see Mr. Pierce, I wasn’t familiar with the show and hadn’t braced for the ending. I walked out trying to articulate my intuition: women’s shortcomings make them a danger to themselves, men’s shortcomings make them a danger to others. Before I could believe myself, I wanted theoretical backing for what I was enduring in practice (and receiving regularly in my text message inbox).

The work most often cited about male loneliness is Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling, Why It Matters, And What To Do About It written by British sociologist Richard Reeves in 2022. Suggestions include encouraging men to pursue HEAL careers (health, education, and literacy), ones that help them to see the humanity in others and reaffirm feelings of usefulness to society. Adjacent pundits declare this is a new issue: men weren’t lonely when they were working in mines and factories or dying in war fields and women stayed at home waiting for them. Even when I set aside the bizarre misogyny of men’s loneliness being women’s fault, I still ran into walls where I’d hoped to find answers.

As has long been the case, academic sociology lacks focus on racial intersectionality. The numbers might be broken down by population density (urban vs. suburban), or by level of education attained (college-educated men vs. those who have only some high school), but there were only crumbs of info about how Black men — the group with which I’m most concerned — are experiencing or participating in this loneliness epidemic. There was no explanation of where my brother, my father, my uncle, my former classmates, my neighbors, or my lovers fit into this bleak picture. I’ve got plenty of anecdotes — dates who seek companionship but seem incapable of making plans, exes who proclaim that they miss me and admit to being afraid of me, my retired neighbor who’s been married 4 times but often reminds me I’m the only one who gave him a Christmas gift back in 2023 — but there is no Richard Reeves of Black men, no movement for Lonely Black Lives. Unless we look into the past to playwright Lonne Elder, III.

Elder’s play Ceremonies In Dark Old Men proves that the “male loneliness epidemic” is a new-fangled name for a chronic condition. Epidemics, like weeds, don’t come out of nowhere and the narratives within Ceremonies point to tangled roots. It’s an old play, pulled from the dusty shelves of 1969 (it premiered ten years after Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin In the Sun) but set in 1950s Harlem, about ten blocks below where I live and write. Besides the cars parked on the street, the block of mostly brownstones probably looks how it did in Mr. Elder’s time.

The patriarch of Ceremonies, Russell Lewis, is a former vaudeville performer and the proprietor of a brownstone barber shop that hasn’t given a shape-up in years because Mr. Lewis has never been good at working. When his legs gave out and he couldn’t dance anymore, he relied on the income of his wife. She’s now long-gone, having kept a roof over his head and that of their three children by working herself sick, but her surviving family have not put her memory to rest.

Her framed black and white photo sits next to her dearly beloved Bible. While everyone speaks of the mother as a God-fearing, hard-working, loyal woman she seems to not have been able to pass on any of these traits to her sons. Bobby (played by the upbeat Jeremiah Packer) is a hood famous thief and his older brother Theophilus is a scheme-enthusiast. Theo puts his half-hearted efforts into an array of shortcuts because seeking a stable job means slaving for The Man.

The only reason anyone in the family has food, clothing or shelter following the mother’s death is her daughter, Adele (played by a subtle Morgan Siobhan Green). When her mom got sick she came home from college to help and got stuck in the role of breadwinner when her mom passed. Everyone agrees that the mother went before her time, having worked herself to death and Adele is wide-eyed at the risk of being driven to the same fate. I gasped in offense when her brothers sneered that she’s “busting 30 wide open” but she’s the only one capable of acting her age.

The show begins in the morning. Mr. Parker, instead of looking like he’s looking for work, is playing his daily game of losing clandestine checkers with his neighbor, Mr. Jenkins. Mr. Parker is clever, so you get the feeling that if he put half as much effort into cutting hair or looking for a job as he does into sneaking around, his daughter would not have to issue ultimatums. When Adele comes home, she announces that the clock is ticking. If he doesn’t find a job she will put him out, old or not. She tells all three boys (I’m including her father here) “you are gonna be happier than you know earning a living for once”.

Theophilus, who is, at times, cartoonishly evil, wants fast money or no money at all. He’s cooked up a plan to make moonshine in the backroom and team up with a neighborhood hustler to launder money in the front. The hustler, named Blue, enters with a blue suit and a matching hat over his processed conk. He’s fly, well spoken, and he proudly introduces himself as the Prime Minister of the Harlem Decolonization Association. He explains that it’s not a well-known organization like the NAACP or the other civil rights groups because they work in secret. The HDA supports the movement by making targets with white faces, selling discount moonshine to bars, and running white businesses out of Harlem through mischief and theft. From his briefcase, Blue pulls out colorful and confusing diagrams, the kind someone would show you right before they ask you to join their Herbalife or Cutco Knives MLM. Mr. Parker falls for it, like they knew he would, and all the men go into business.

Soon, Theo finds that it’s called hustling for a reason, and it isn’t as glamorous and easy as he had imagined. He sweats in the backroom distilling moonshine around the clock, while his father is buying fine clothes to run the streets with much younger women and enjoy what he thinks is the end of his life. Even worse, Theo is running interference between his father and Blue; one is skimming off the top and the other is starting to notice.

As the show unfolds, it’s no wonder why Mr. Parker loses at checkers every day. He’s a sucker for his son’s short-sighted schemes, Blue’s diagrams, his daughter’s entreaties, and the young women who dangle promises of intimacy in exchange for information about his business. He doesn’t even see how each of these competing interests would make it impossible for him to satisfy everyone. There’s something missing inside of him, perhaps the years of the old soft-shoe routine has ruined his knees and rattled his brains. He can’t see more than two steps ahead of his current situation; it’s a wonder he had the sense enough to ask his wife to marry him.

This felt like the next pearl in a string of plays serving a sobering reminder that “things don’t change, they just stay the same”. Watching Bill in Wine In the Wilderness was Youtube’s Pop the Balloon show viewed through a retro filter; Theo in Ceremonies feels like listening to a podcast bro, streaming live from his mother’s basement, explain how Black women and The Man don’t want him to be great. It’s beginning to feel, after years of imagining of what it might’ve been like to be ‘in the room when it happened’, that it wouldn’t be all that different than what I’m living through now: masculine disenfranchisement, overt and subtle racism, and Black women left holding the bag.

At a particularly tense moment in the show, one of the characters remarks, “Who the hell told every Black woman she was a goddamn savior?” And I have the same question. I so badly wanted Adele to get up and leave, to kick them out and change the locks, to finish the college education she started before her mother got sick, to find a love that offers rest. But who’s to say that the man she’d find wouldn’t turn into free-loading redo of her brothers and her father?

(Even I — someone who’s proud to have both a brother and a father that I deeply respect and whose support I’d gladly reciprocate — shudder at how close I’ve come to falling into a trap of loving someone that you have to raise.)

Ceremonies was a nominee for the Pulitzer Prize in Drama in 1969, though The Great White Hope would ultimately win the award. Hope is a fictionalized retelling of pioneering Black boxer Jack Johnson’s career in and out of the ring. It was written by Howard Sackler, who is white, and starred James Earl Jones. Four years later, Mr. Elder would be the first Black person to earn a nomination for an Academy Award in Writing for Lady Sings the Blues. Elder’s writing is what gives this play complexity and legs. Though the dialogue is steeped in its 1950’s time period, Elder’s storytelling is present and timeless. That Ceremonies has circled back around and rankles me the way I imagine it would’ve rankled a Black woman in ’69 is strangely soothing.

Some of the performances in this 2025 production live up to Mr. Elder’s vision. Norm Lewis, of course, is indomitable in ways that sneak up on you. He draws your pity and forgiveness even as Russell Parker makes one silly choice after another. Parker likes what he likes — checkers and chasing skirts — but Mr. Lewis makes you love him for it. Lewis plays Parker as an endearing oaf, a playful imp; he’s a dancer, not a businessman, not a devoted father.

His companion Jenkins, played by James Foster, Jr., feels like he walked directly out of the era. His Caribbean lilt and comical sheepishness about getting caught goofing off with Mr. Parker felt just as sincere as when he delivers the worst kind of news at show’s close. I wanted more from both Blue (Calvin M. Thompson) and Theo (Bryce Michael Wood) in their most aggravated moments. I wanted to see more fear when one holds a knife to the other’s neck and I found Theo’s bursts of rage unfounded. I couldn’t understand what motivated him: was it money, power, respect, sticking it to his sister? Without understanding Theo’s motivations it was hard, from where I sat, for all of the pieces to come together.

When I put myself into the shoes of any of the characters, I can feel the impossibility of their situations. Adele can’t abandon the men in her life when she knows those knuckleheads lack both the skill and the gumption to make an honest living.

Mr. Parker is stuck in a former lifetime and can’t free himself from his same repeated stories about the long ago best moments of his life. He’s grieving his wife and his short-lived dreams.

But Theo, the mastermind who brought danger to the family’s door, has created the corner he chooses to live in. I can’t relate. Black women are too busy being everyone’s savior to indulge daydreams of word domination, but if I were so preoccupied with power that I’d convinced myself that I didn’t have any, I think that I’d feel lonely, too.

blacklove 🖤 and starlight 🌟

The 2025 production of Ceremonies in Dark Old Men was produced by The Peccadillo Theater Company and Eric Falkenstein at the Theatre at St. Clements. This production was directed by Clinton Turner Davis and starred Norm Lewis, Felicia Boswell, James Foster Jr., Morgan Siobhan Green, Jeremiah Packer, Calvin M. Thompson, and Bryce Michael Wood. The play was written by Lonne Elder and produced by the Negro Ensemble Company, Inc. in 1969. I received a press ticket to this performance and attended on June 2nd, which also happened to be Mr. Lewis’s birthday. Ticket prices begin at $39.

- I got a kick out of the vintage seats at the theater.

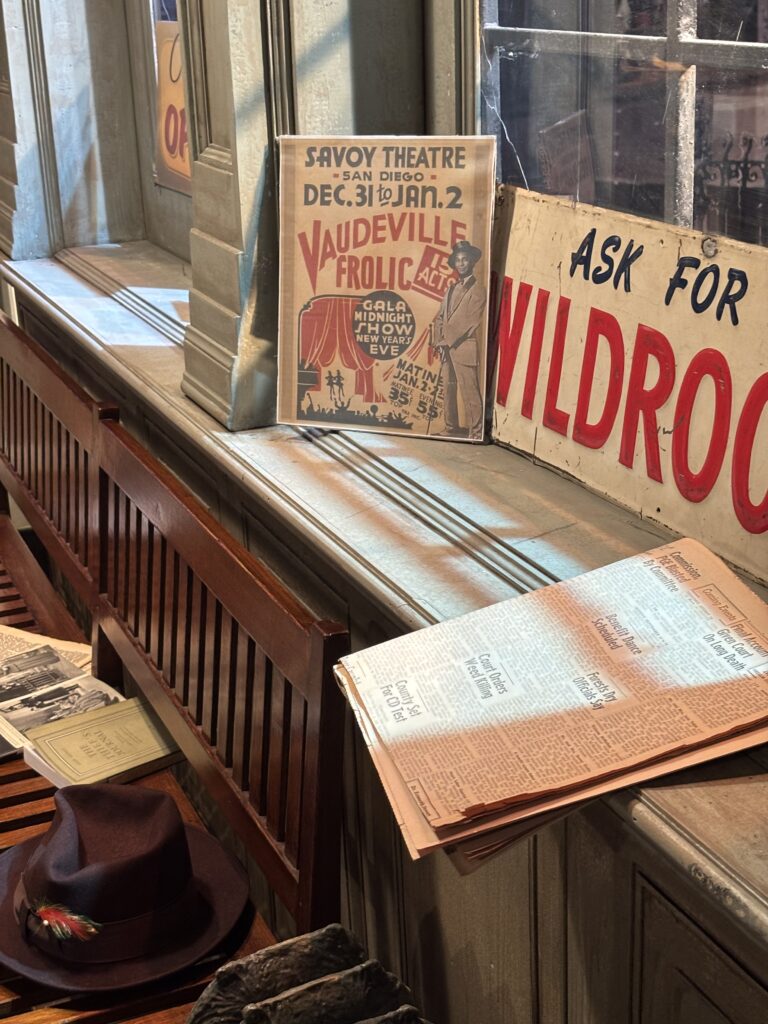

- The attention to detail in the props helped the show to feel grounded in its intended time and place.