“Purpose” Broadway Review

You can’t carry on emotional baggage like this. Somebody’s going to get checked.

At least three times over the loudspeaker, we’d heard the flight attendant request that people check their carry-ons and nobody moved. Why heed their threats of limited space? Why risk slowing the choreography of airport escape with a pit stop at baggage claim? I sipped a Diet Coke and silently counted the roller boards in my waiting area.

There were business travelers, school groups, and families in shades of amiability. Selfishly, I wished the families a peaceful trip — not only so that I might enjoy a quiet flight but also, as I approached the beginning of five days at sea with my own extended family — for karmic exchange. After what I’d seen the night before, I wasn’t sure I could stomach any secrets or hold my tongue if insults started to fly.

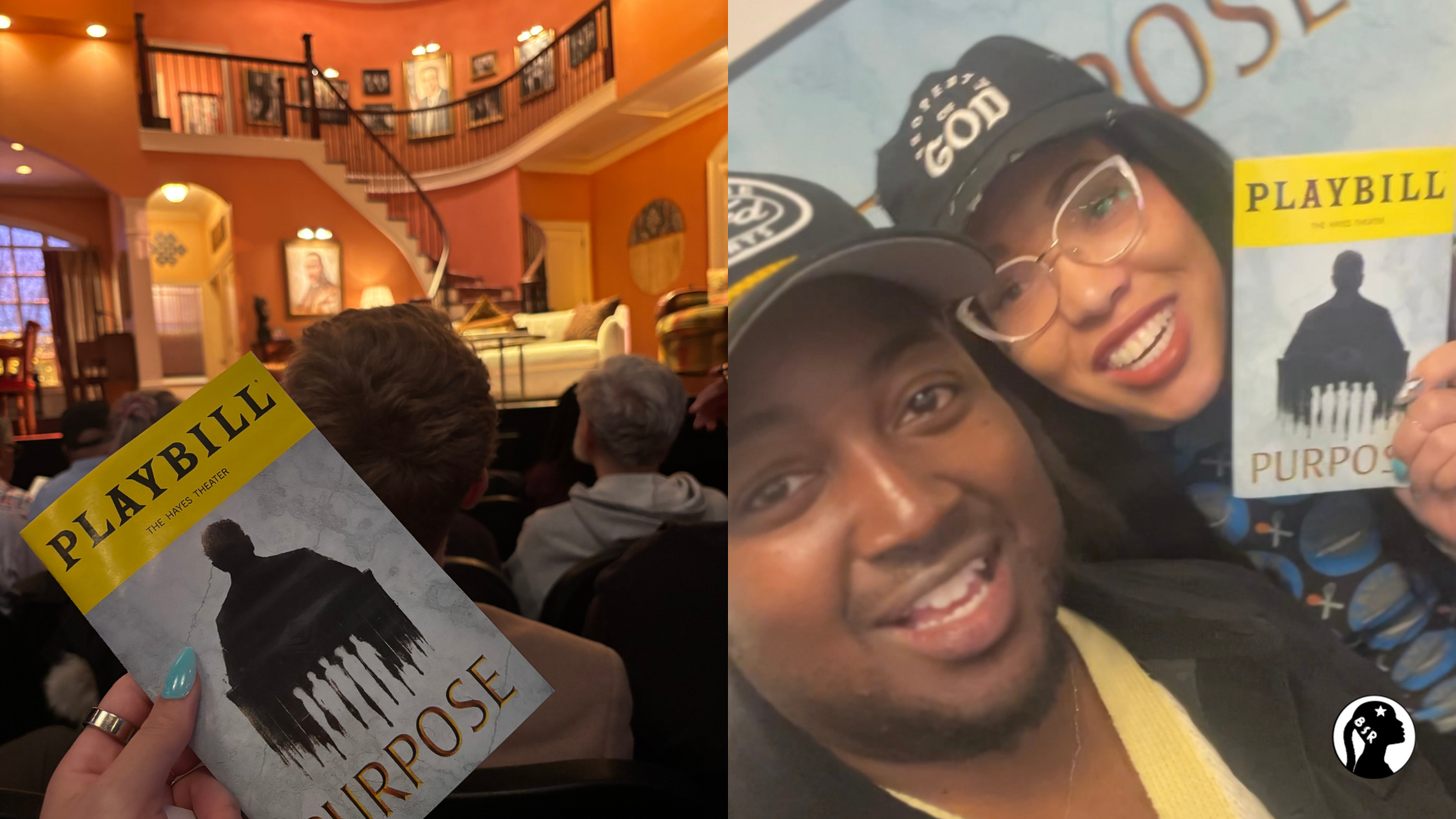

I hadn’t intended to sit front row and center to family drama hours before I left on my own family vacation, but I really should’ve remembered what playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins does best: writing families into audible-gasp, blush-from-your-seat chaos. By intermission, Donavan and I were questioning strangers in nearby seats because we had to know: What would it take for you to lay hands on your in-laws?

But before I fix my mouth to talk bad about anybody else, let me air out my own dirty laundry: this wasn’t the show I’d set out to see. I’d arrived to the box office bright and early to see a certain someone guest star in a certain award-winning comedy, but when I ended up being six people too late for rush tickets, I trudged around looking for second fiddle. (If I’d walked a little further, this review might’ve been about BOOP!) The Hayes, a theater that’s always affirmed my belief that I have good luck, came through. Two seats, center orchestra, Sunday evening. Six relatives each with individual motives and a psyche filled with weapons are trapped inside during a snowstorm. What could go wrong? It’s like a Black game of Clue, family reunion edition.

Previous to this, I’d seen 3 shows by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins each more impressive than the last, like a cake amassing tiers. This new layer is definitely red velvet, a special occasion staple for Black families, not that I could eat it in peace if Branden was around. If he were kin to me, I’d be careful to comport myself and cautious of what I’d let slip at any Jacobs or Jenkins family gathering. I imagine his memory is a chest of index cards, on each a quip, an action, a reaction, a secret, that he can put to use on stage. His family reunion t-shirt would have to be a neon bright; we’d have to put a bell on him so we could hear him coming. Shush that talk around Branden else he’ll write you into one of his lil shows.

The story begins with a monologue from our main character, played by Jon Michael Hill. He’s a nature photographer who goes by Naz, which is a shortened version of his full name (and Jesus’s hometown), Nazareth. He’s headed home to Chicago from New York by way of Niagara Falls, fresh off a photoshoot in the Canadian wilderness. He’s arrived at his family home courtesy of his homegirl Aziza (Kara Young), who despite their platonic connection, has asked Naz to be her sperm donor via turkey baster. This information is delivered casually, as if everyone in the audience has made a baby this way, and it’s followed up with another juicy bit of backstory. The occasion for the reunion is that Naz’s older brother Junior (Glenn Davis), who got hemmed up in political fraud, has been released from prison. Junior was using campaign funds for luxury purchases and private plane rides and he doesn’t deny his guilt nor shoulder any shame for this victimless and (if you’re white) usually unpunished crime. After these casual updates, Naz warns us in the same clipped tone of a liaison who’s about to take you behind enemy lines, that things in this house can get intense quickly. And from your seat you wonder, seeing as how he’s already disclosed his brother’s criminal history and his unconventional reproductive relationship with his neighbor and home girl, how much more dirt could there be? Immediately and repeatedly, you will eat your words. The only gulp of relief to wash it down is that it’s their family and not your own.

“Purpose was a hilariously serious and good time. So many familiar moments made it feel like I was watching my own blood on stage.” – @chefdonavan

As always in a Jacobs-Jenkins play, the language is precise and poetic. The insults impress as much as they incise (and if you’re trying to nab little fragments for your notebook in the darkness of the orchestra, you’ll feel like giving up.) The patriarch of the family, played by Harry Lennix with a stirring dose of ‘zaddy’ energy, is especially likely to deliver the erudite heat. He is after all, a Civil Rights era pastor. The swooping staircase nods to the family’s bourgeois background — these are, or at least were, moneyed Blacks — but the photos cramped onto the wall behind the stairs lets you know they’re just like you and me… at first. On closer inspection, the curation reveals an array of the Reverend Sonny Jasper photographed shaking hands with notables like Mandela, Jackson, and Sharpton. The only solo portrait that rivals the Reverend’s in size is Dr. King’s, but even then Reverend Jasper takes top billing. Sonny lords over the second floor as Dr. King is relegated to the first.

Poor Dr. King, trapped in a picture frame with a front row seat to all that’s revealed around the family table. It’s a full house tonight. Aziza has returned to the house after dropping Naz off; she comes inside to return a phone charger and ends up receiving a dinner invitation. Because Naz has never brought anyone home before, the other Jaspers are rabid with curiosity and hope. Aziza’s curiosity is piqued, too, once she finds out that Naz is a “nepo baby”, the seed of a ‘Famous Black’, the kind that had entire Black History Month lessons dedicated to their honor. Though he’s shared his sperm with her, Naz never saw fit to tell Aziza this lineage or even his full name, which would’ve been a dead giveaway as to who his people were. Also, at the table is Junior’s wife, Morgan, who’s cloaked in oversized sunglasses and apathetic about her husband’s release from prison since his return starts the clock on her departure. (Credit here to costume designer Dede Ayite for Morgan’s comically large sunglasses and Father Jasper’s velour Telfar sweatsuit.) Morgan (Alana Arenas) was found complicit in his fraud and the judge agreed to let the two serve their sentences consecutively so that their children would have one parent present during this tumultuous time. A father, two sons — one a convicted felon, the other a seminary school drop out — their mother, one wife in mourning and one aspiring mother-to-be. You can’t carry on emotional baggage like this. Somebody’s going to get checked.

Each of the characters Jacobs-Jenkins has written is both psychically rich and immediately recognizable. The aging Civil Rights leader who (allegedly!) parlayed his influence into extramarital affairs. He may or may not have slipped out the back after a speech or two, plowing the path to laying-down liberation with many a fervent follower. The politician who saw his elected office as a stage on which to perform and was shocked by the expectation of governance, morality, and personal ethics that comes with the job (or used to…) The man — adult in stature but underdeveloped in emotionality — who’s felt he never fit in in this family, who’s sought silence in the uproar of conflict and the outbursts of joy. None is more complex than the mother who has long played the background, but at least in this review, she will have her time in the sun.

In the show, her crime is the lengths to which she’d go to preserve her family’s legacy. She won’t lie on you, but she’ll intentionally deceive. She won’t physically harm you, but she’ll hand you a rope with a smile. Maybe she’s a mother, maybe she’s a control freak, maybe she’s a just a lawyer. Altogether, it’s a suffocating combination.

Outside of the show, the crime is all the time I’ve spent watching Samuel L. Jackson onscreen, when I could’ve been seeing his wife and fellow actor, LaTanya. Why did they make us choose between them when we could’ve had both? Ms. Richardson Jackson fills the Hayes with her fervor and even when she feigns tears you’re inclined to hand her your own handkerchief. Naz is clearly our imperfect protagonist, but it feels impossible to identify the villain in this story because the obvious choice (mom!) is so well-played it brings the motives of every other character into question. (In addition to well-played, the show is well-written. Jacobs-Jenkins is best-in-class at crafting relatable villains). It’s the mark of a master manipulator who can make you think that you’re the problem even when confronted. I had to remind myself repeatedly that Ms. Richardson Jackson was in character, even when every line delivered and every deliberate movement seemed to derive from original thought. It’s difficult to explain but I’ll try: She’s acting when the spotlight is on her and when it’s not. I’ve never seen an actor so clearly internalize a character’s thought process that you can see when she is thinking and what she is thinking without the need for a monologue. She’s loudest in her quiet moments. Credit is due to both Ms. Richardson Jackson and the director, Phylicia Rashad, for giving the Claudine character such a wide and regal berth.

In all my admiration for Jacobs-Jenkins, I can admit his endings feel like a film’s slow fade to black over an anticlimactic panoramic shot. The credits roll without any real resolution, leaving the audience to tie the loose ends on their own. Families are messy, and life is messy, so maybe this is not the end of the world, but this show starts out with an ambitious pitch and then relies on the final moments to close the deal: deliver a theme, unpack the title, and lay the story to rest. In the closing scene, Naz has a conversation with his father where he can finally speak freely about his sexuality, his choice to leave seminary school and keep it a secret, and his preference to spend his time alone in the woods. The men connect over their affinity for nature, Sonny has taken up bee-keeping in his retirement. Both men are seeking a new definition of purpose but up until this scene, it wasn’t clear that purpose was something Naz was grasping at. It’s not like he’s been flailing since dropping out, he’s found contentment and satisfaction in his new profession. In an earlier work, Jacobs-Jenkins ends his play with a tree growing in the center of a house. It’s surreal but poignant the way the roots and limbs shatter windows, disturb floorboards, and destroy furniture. In Purpose, the ending trembles behind the bravado of the climax. In comparison to the center stage tree, it manages to be quieter and less meaningful, but just as messy.

I stood at the baggage claim in Houston surveying the familiar faces from the boarding gate in New York, those who’d gambled on overhead space and lost. The slow circuit of the luggage carousel is a consequence I’m willing to endure, it’s either this or hours in the bathroom at home waiting for soap and sunscreen to slide into travel sized tubes. That, and I never saw much value in squeezing and sweating over the smallest possible bag. In packing as in family dynamics, you run the risk of an explosion on the unzip.

blacklove 🖤 and starlight 🌟

The Broadway production of Purpose will run through July 6, 2025 at the Hayes Theater. Tickets range from $45 (rush) to $299. I attended the performance on March 23, 2025.