“Wine In the Wilderness” Review

Sitting On A Secret

Sometime in 2024 I received press tickets to attend a play with a Black cast and creative team that had gotten rave reviews from all of the major publications. Since the loudest voices in the city were calling the show a reclamation of Black love, I went into the theater feeling hopeful. I mused that the show might soften and motivate me to reconcile with an ex, make time to swipe, or turn off my RBF long enough to have a meet cute in a coffee shop. Here, I thought, is where it all changes for me. Here is where I begin to believe in love again.

But like many an ill-fated relationship, all my hopes came crashing down when the play the city had been crushing on turned out to be a shallow farce. My friend and I left the show incensed. I didn’t want to write my review and delineate the reasons why I thought the show was toxic. And I really didn’t want to have a negative opinion of a show and a story that was rooted in Black creativity, at least not publicly. But I gritted my teeth and chose honesty. Naturally, none of my thirty-odd viewers on YouTube made a peep either way.

A few days after I posted my review, I was stepping outside of my front gate, cueing up the soundtrack for my morning commute before hustling to catch the train when I saw — on my own block — the leading man from the show. I’m spot-on with faces, so I started with a question I already knew the answer to.

“Excuse me, are you BLACK ACTOR?”

“Yeah,” he said with a smile.

“Wow! I just saw you in PLAY TITLE.”

“Oh whoa, that’s random. I was just on my way to move my car.”

“Yeah, that’s really crazy. I live on this block.”

“So, what did you think of the show?”

“Can I be honest?”

“Of course.”

“I thought it was toxic. Your portrayal was excellent because even as I’m talking to you now, it’s hard to separate you from ROLE but the relationship you had in the show was so hard to watch.”

“Yeah, you know you’re not the first person to say that. A few women have told me after the show that they hate me. And my mom came and saw it and told me she thought it was kinda misogynistic.”

“Yeah, I mean…I can see why….it was hard to write about.”

From there, he gave me his Instagram handle so I could send him my review and that was the end of our exchange in person or otherwise. I don’t know if he opened the message and I don’t know if he watched the video (but the playwright did leave a heart comment on YouTube!)

This interaction rolled around in my mind like a glass marble for weeks. His mother’s opinion confirmed that I wasn’t crazy or hyper-sensitive, but knowing this only made things worse. If both she and I thought the play was misogynistic, then what kind of hard drugs were the people at the NYTimes and Time Out smoking?

But what could I do with this information? It didn’t seem right to hop on Instagram and tell all him and his momma’s business. Plus, I don’t know the rules about being on/off the record and I don’t want to people to feel wary of what they share with me in passing.

It would’ve been messy to post a 1-minute video saying “I just met BLACK ACTOR on the block outside my house and he told me that his mom thinks PLAY TITLE is misogynistic, what was this PLAYWRIGHT thinking and why does this feel like a conspiracy to promote unhealthy relationships in the Black community?!”

So I just sat on it.

Until now.

Because today I’ve seen something so much worse. I never thought I’d see a more blatantly toxic portrayal of Black heterosexual gender dynamics, but here we are. Now, both PLAY TITLE and Wine in the Wilderness deal with problematic dispositions and feature (disgusting!) portrayals of entitlement, but I left Wine with peace in my heart. I won’t be comparing these two works, not only because it would be pointless if I won’t name the other show, but also because Wine In the Wilderness deserves its own review. [If you figure out what show it is, you can do the comparison on your own and send it to me. I’d love to read it.]

Alice Childress: A Woman On A Mission

Let’s start with intent. Wine in the Wilderness was written in 1969 by Alice Childress. Alice, whose life story and accolades are material enough for their own post, passed away in 1994 after a full life as an actress, a playwright, a columnist, and novelist. It seems a number of her plays were written to prove a point. Her Wikipedia page says she wrote her first play Florence to “settle an argument with fellow actors (Sidney Poitier among others) who said that in a play about Negroes and whites, only a ‘life and death thing’ like lynching is interesting on stage” and cites a 1969 book on Negro playwrights by Doris E. Abramson for the quote. The program for Wine in the Wilderness includes a letter from CSC’s Producing Artistic Director, Jill Rafson, that says, “Childress was an actress who didn’t see roles being written for Black women like her, and she didn’t see stories on stage that reflected her world and the questions that her community was facing every day. So she wrote them herself.”

That’s one way to put it. You might also say she could see the future, because the most unnerving aspect of this play is that the questions her community was facing every day have not been answered. They’re the same questions far too many people with a platform have been using to ask such silliness as:

- What’s wrong with Black women?

- Why do they wear wigs?

- Why can’t they “build up the Black man”?

- Why do they have to have opinions?

So Alice went into this play with a point to prove and to be honest, I think she scored a few three-pointers from all the way downtown.

A No Spoiler Summary of Wine in the Wilderness

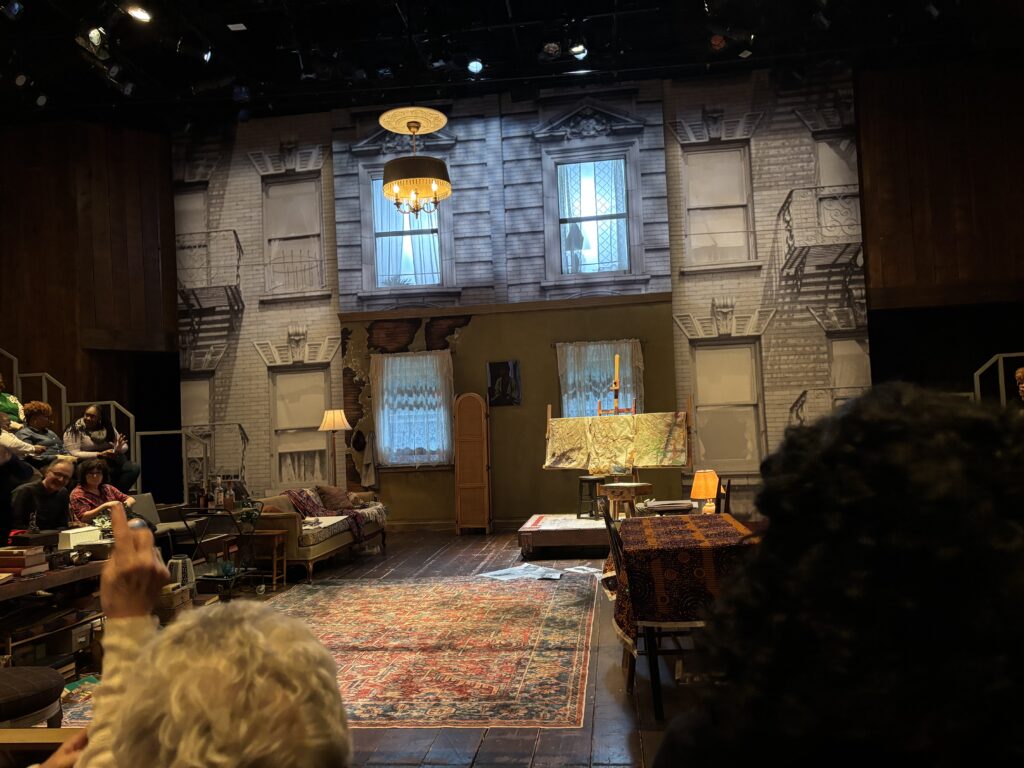

The play opens with Bill painting in his Harlem apartment while a riot goes on just outside his window. (Childress did not invent this background event, there were seven days of rioting in Harlem over the shooting of Black teen James Powell by the NYPD.) On the street, people are protesting, fighting, looting, and setting things on fire, but not Bill. He’s inside ducking from the windows and thinking about working (but not getting much done).

When he hears a knock at the door, he’s worried there’s violence on the other side but it’s just an older guy from the neighbor who they call Old Timer. This grandfatherly guy is not one for shattering windows, but he’ll reach through the holes other people create to grab a few things for himself. He and Bill drink to Bill’s work in progress, a triptych of Black womanhood. A triptych, which he explains to Old Timer (and the audience since many of us do not use this as an everyday word), is three works of art intended to be seen together or make up a piece. He’s got two of his three triptych panels finished.

The first panel is a Black girl. She’s pure and innocent and she represents the beginning. The second panel is the pinnacle of Black womanhood. She is truly of the continent, a completely natural woman with a deep complexion and a feminine disposition. She is an African queen. She, Bill announces, is “wine in the wilderness”. This is not a woman Bill knows, but one that he — a divorcee — dreams to one day have. Bill unveils the third panel with a flourish only for us to see that it’s blank because he hasn’t yet found a model.

While you might predict that the third panel will be an elder, making the triptych about Black womanhood over time (childhood, adulthood, old age) Bill has something else in mind. He wants to use the final panel to depict the anti-Black woman, the thing Black women should aspire to least but become all too often. He imagines his triptych will be hung in a post office or a library so that little girls will see themselves on the left and grow into the woman in the center, cautious to avoid becoming the woman on the right. He describes this yet-unpainted woman as being “as far as she can get from an African queen and still be female.” Woof.

In the middle of the riot, Bill’s friends think they’ve found the perfect woman to sit for the portrait. She’s a woman who is “back country, but raised right here in Harlem” and they ignore Bill’s animated attempts to decline, saying they’re on the way to his apartment with the woman they’ve found. Here, the audience has just enough time to create a mental image of the woman Bill describes. She should be a woman so unpolished, so distasteful that she’s a drag on the entire race. When the door opens, we see Bill’s friend, Sonny-man, his wife, Cynthia, and the woman they found at the bar, Tommy.

Tommy is there under the impression that this is a dating set-up. She’s single and hopeful for a husband, even though she’s older than the “marrying age” at the time. She wants Bill to like-like her but Bill wants only one thing: to finish his artistic statement on which Black women deserve respect.

Things escalate as the night settles in. During a moment alone with Cynthia, Tommy asks for advice on how to get a man like Bill to take an interest in her. Cynthia, Sonny-man, and Bill are with The Movement —they’re educated Blacks. They’re the kind that go to marches, read books, and have jobs that require degrees, like a social worker. Tommy didn’t finish school and she’s corrected by the others to say ‘Afro-Americans’ when she refers to the people who’ve destroyed her home as ‘niggas’. Cynthia gives Tommy all kinds of advice about how to attract Bill and all of it is in direct opposition to who Tommy has had to be in order to survive. Tommy’s used to speaking up for herself, but Cynthia says be less brash. Tommy’s used to taking care of herself, but Cynthia says this makes her less feminine. Cynthia never mentions the real reason why Tommy shouldn’t care too much about what Bill thinks: that she’s only there to be the standard of deplorability in his impending masterpiece.

When the others leave, Bill struggles to paint Tommy when, at his request, she begins to tell him about herself. Despite his frequent insults, she begins to lay bare a vulnerable and intelligent side that makes it difficult for him to find the twisted inspiration he needs for his last panel. The two begin to form a connection beyond that of an artist and his muse until Tommy learns Bill’s true intent and that everyone else was content to see her be exploited.

It’s Me, Hi. Bill’s the Problem, It’s Bill.

When you see the play, you’ll get to find out for yourself how Tommy learns the truth and how she reacts. While you’re at it, I’d suggest you take note of your own reaction to the ways Bill and Tommy interact. Since I was already taking notes for my review, I wrote down everything Bill said that started with, “That’s the problem with our/Black women, they…”

According to Bill, the problems with Black women are: we’re always worried about food, always want to eat fast, always want to have a big brain (instead of leaving something to the men), too opinionated, and want to latch on to you until you’re in the grave. He never mentioned that Black women were violent, so maybe he wouldn’t have seen it coming if I’d taken the pointy end of a paintbrush to his eye.

Childress makes it exceptionally clear that Bill is not the prize. Though he has an apartment filled with books, he’s educated, and he grew up middle-class in the suburbs of Long Island, Bill is emotionally unavailable and spiritually impoverished. Ladies, beware. He’d prefer to paint his perfect woman on the canvas; if she existed in real life he’d surely find a flaw as soon as she opened her mouth. After all, women need to put their big brains to sleep and let the men have something. Bill is in the wilderness, but he sho’ doesn’t deserve wine.

On the other hand, Childress turns the entire Tommy narrative on its head the more we learn about her. She’s not some aping she-oaf, lumbering around Harlem like a loud-talking promiscuous circus freak — she’s a beautifully human woman who’s shown resilience when faced with the kinds of troubles that Bill, Sonny-man, and Cynthia have never, and likely will never, face. Here were all of these educated Blacks calling her ‘sister’, luring her with the possibility of love on the day her apartment and everything she’s ever owned has been burned down. From where they stand, if Tommy doesn’t wear her hair natural and can’t quote Brother Carmichael, she deserves to be humiliated because, to them, she’s already choosing to humiliate herself. In their minds, the only way forward as a people is strict adherence to a particular performance of Blackness and those who can’t learn the script are cut from the cast. Only Black Excellence will help us to the Promised Land.

Lo, I say to you, when will it end? Why are we in 2025 still parsing through the same critiques we faced in 1969? When will we see each other as Black enough, feminine enough, intelligent enough, resilient enough, human enough? There will be no Movement if we’re turning folks away at the door for respectability politics like it’s the Turkey Leg Hut. And to underscore that point, you should know that the infamous Hut closed permanently in November 2024. If you told me Childress wrote this play yesterday, set during the BLM riots of 2020, I would believe you. The fact that this play is still relevant after more than 50 years means that at the rate we’re going, we’ll Booker T./Dubois ourselves to death. All this talk of boots and straps, which way to go and who should be in front, meanwhile The Movement advances at a snail’s pace.

A significant part of the reason why I left this show feeling more comforted than disquieted is the solution the play presents in its resolution. It’s not about the Tommy forgiving Bill’s emotional violence as ‘quirky’; she’s not forced to sacrifice her own self-worth to fit onto his canvas. There is an ongoing community-wide conversation about what we bring to each other in partnered relationships (hetero or otherwise), which means that individual dynamics are only a drop of wine in a glass of water. What happens in your bedroom is your business, but the slow dissolution of our collective love lives is liberation work. By the end of the show, the characters have figured this out. In this way, Childress has written an idealistic future we have yet to realize on this plane: everyone has something to give and in community is the most beautiful place you can be.

Closing Thoughts: On Actors, Artists and Titles

It’s a testament to the performers that Childress’s intended nuance travels from the stage to the audience, from her present to ours. Even the white woman next to me gasped when Bill began his tirade about Black women’s problems. Bill, played by Grantham Coleman, harnesses equal parts sensitive artist and Kevin Samuels if he had lived long enough to reach redemption. In Coleman’s attendant depiction of the moment Bill comes to his senses, we get to watch realization dribble down his face. Olivia Washington gave a moving performance while being both too earnest and too gorgeous to be believable as the rough-around-the-edges type Tommy is implied to be. In the role of Oldtimer, Milton Craig Nealy strikes a heady balance between senile and sharp as a tack (which so many of my elders are good at and yours as well, I’m sure). Lakisha May and Brooks Brantly didn’t have a lot to work with in their supporting roles, but gave just enough sly knowingness about Bill’s plan to help build intrigue. Overall, the director, LaChanze, ensures the messages gets across to modern audiences. She’s no stranger to Childress’s work, having earned a Tony nomination for Best Actress in a Play in the 2021 revival of Trouble In Mind which Childress wrote before Wine in 1955. I’ll be curious to see if LaChanze continues working with Childress’s material; I’d certainly like to see more of her work on stage.

The titular phrase, Wine in the Wilderness, is used so many times in the play that I made a note to look into the origin after the show was over. In addition to being the name of an annual event at the Utica Zoo for the last 23 years, it’s a paraphrase of a line from a poem written in the 11th Century. Omar Khayaam, a Persian Poet and mathematician, wrote hundreds of four line poems called quatrains in Farsi that were eventually translated to English by Edward Fitzgerald in 1859. The phrase appears in verse 12.

A Book of Verses underneath the Bough,

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread—and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness

Oh, Wilderness were Paradise enow!

In my interpretation of the verse, Khayaam dreams out loud: a book, wine, bread and my lover singing next to me would make any wilderness a paradise.

The idea of wine in the wilderness also appears in the Bible in 2 Samuel, Chapter 16. King David meets another man’s servant, Ziba, outside of the city. The servant has a heap of resources — donkeys, bread, cakes of raisins and figs, and wine — and David asks him what they’re for.

Ziba answered, “The donkeys are for the king’s household to ride on, the bread and fruit are for the men to eat, and the wine is to refresh those who become exhausted in the wilderness.”

He gifts all of these resources to the King and David responds that Ziba now owns everything that belonged to his master.

I don’t know which verse Alice used to speak life into Bill, but I appreciate the way she uses this work to address misogyny and misogynoir head on and ahead of her time. Fifty years later, Bill still feels real. He feels so real, in fact, that I can imagine interviewing him in his studio like I have other painters and artists. I hope he’d bring up “Wine in the Wilderness” so that I can ask him about his inspiration. I’d share both verses and follow with a question, on the record. Do you see Black Women as the thing you consume to fight exhaustion on your way to the Promised Land or are they the ones with whom you can make any place a paradise and share a little bread, some wine, and a song?

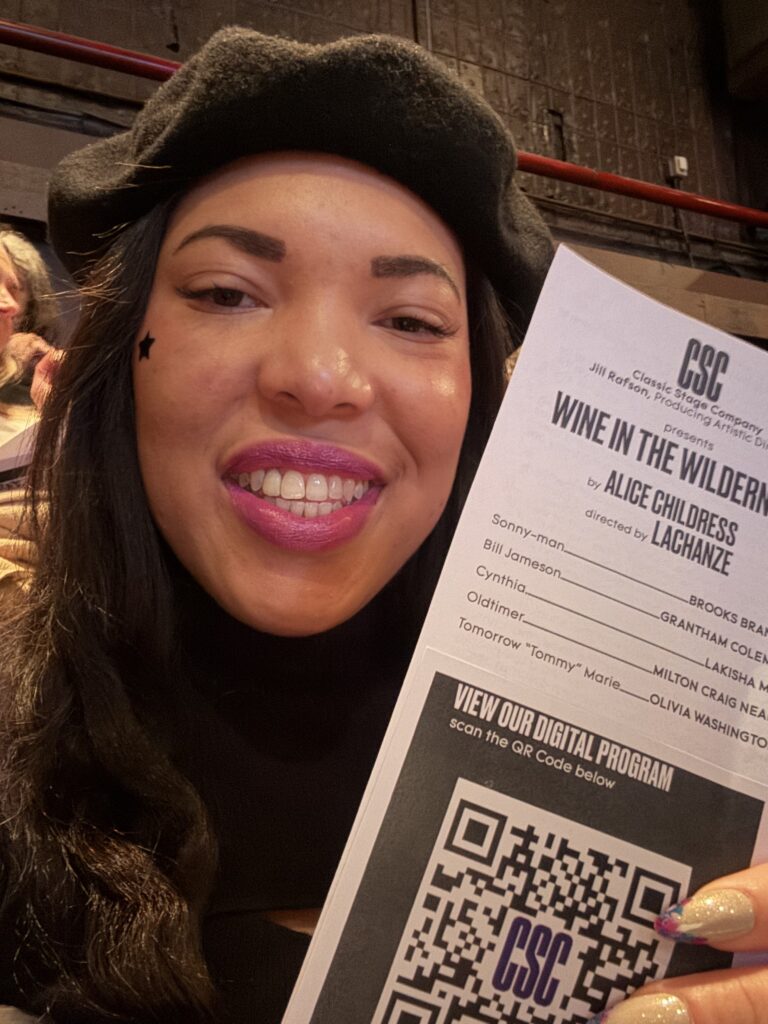

Wine in the Wilderness was written by Alice Childress in 1969. The 2025 production of the play by Classic Stage Company was directed by LaChanze. This production of the play will run through April 13 at CSC’s Lynn F. Angelson Theater near Union Square. Tickets range from $76 to $132. I attended a preview of this performance on Saturday, March 15.